Saturn’s Mysteries

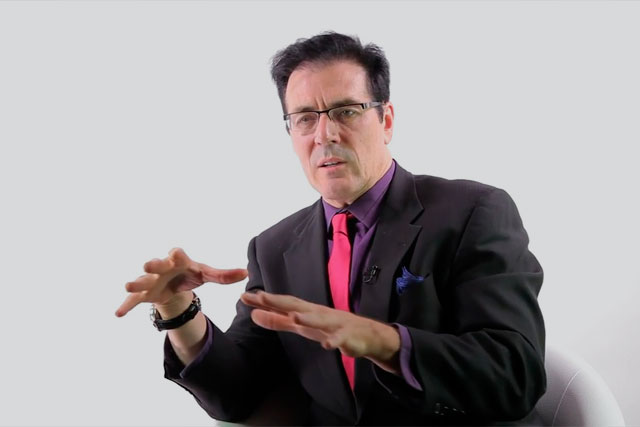

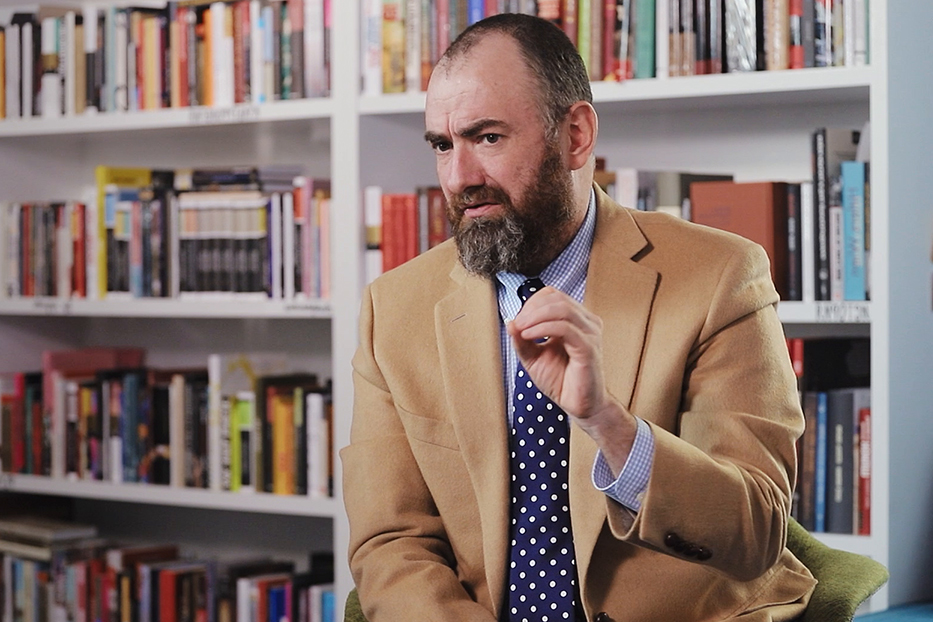

Physicist David Southwood on the origin of Saturn’s rings, the length of the day on Saturn and why the magnetic field of Saturn is so strange

videos | June 4, 2020

Saturn, for me, is the most beautiful object I know in the sky. I can remember the first time I ever saw it through a telescope; I looked and just couldn’t believe this view of this planet and its rings that make it special at first glance. How can something as exotic and beautiful as that just be sitting out there not so far from us on the scale of the Universe?

So I’ve always had a liking for Saturn, and then, of course, with the Cassini mission, I found I had a very distinct interest in the science of Saturn. It’s true that the Cassini mission has removed some of the mysteries of Saturn: it’s counted the number of moons, it’s seen what the rings are made of and so on. On the other hand, as often happens, there are as many discoveries as there are new questions asked. It’s like when you’re hiking: you come to a range of hills, you get to the peak of the hill, and you look into the next, and you see there are more hills beyond. I think it’s fair to say that Saturn still has mysteries to be resolved.

Some of the mysteries will be resolved by analysing all of the data that we took over the last 15 years with Cassini: it’s just we haven’t analysed it all, so there is more to come in terms of exploration but there is surely going to be mysteries remaining.

For me, the first mystery was the rings. What are they? Are they the beginning of a moon or the end of a moon? How long have they been there? Some of the latest results are that the rings are relatively recent, and so I think it’s maybe 10 or 100 million years old, which sounds like a long time, but not when you remember the Solar system is 4.5 billion years old. So, the rings are relatively new. No human has ever seen Saturn without its rings, but if the dinosaurs had had a telescope, they would have seen Saturn without rings. That, for me, is a magical thing, very surprising: the rings are relatively young. We found that out by the analysis of the mass of the rings. The way we could understand the mass of the rings was at the very end of the Cassini mission by taking the spacecraft inside the rings and looking at the very subtle changes in the orbit of the spacecraft due to the change of gravity because you’re passing inside the gravity of the rings.

It turns out the only way you can make a magnetic field continuously is if it’s asymmetric around the centre; you can’t make it purely symmetric in all directions. So somehow or other, within Saturn, there’s a process that is asymmetric and somehow above that, there’s something going on in the interior of Saturn that hides from us these things that we know must be there. The extraordinary thing is that although the field is axially symmetric, as Saturn rotates, the magnetic field doesn’t change if you sit at one point because it rotates exactly like the planet. No other planet has been found really like that.

But then it turns out that the north-south symmetry along the rotation axis is asymmetric. We feel the axis of the symmetry point north-south is shifted quite substantially off the centre of the planet. That’s another puzzle.

It’s almost as if Saturn, before we got there, said, well, let’s look what planetary scientists have predicted and just show that they’re wrong.

There’s an awful lot of work to be able to reproduce this magnetic field. There isn’t any query what the field is; there is a query as to how it got there.

If that’s one mystery, the next mystery I would say is why, if you’re outside Saturn and you measure the magnetic field, can you see that the magnetic field appears to be rotating? It has nothing to do with the interior of Saturn: it’s somehow associated with the northern and southern polar caps that rotate at slightly different rotation rates and somehow make a magnetic signal far out from the planet but do not give us the rotation rate of the planet but the rotation rate of the upper atmosphere which is something different.

Indeed, to the embarrassment of the magnetometer team, I would say the length of the day on Saturn has not been determined by the magnetic field as you would expect it to be everywhere else. For example, the most accurate way to measure the length of the day at Jupiter is from the magnetic field. But no, in the case of Saturn, it’s from the gravity in the rings that tells us the day is 633 minutes plus some seconds long. In the case of the day measured by the magnetic field, believe it or not, there are two periods: one for the northern hemisphere and one for the southern. It varies with season; with summer or winter, it ranges between 636 minutes and 648 minutes. I think I’m at the point of being able to solve that problem and explain why we get these external magnetic signals that give an illusion of knowing the time of day, but it’s an embarrassment for a magnetometer person that the final time of day at Saturn has been given by the gravity team on the Cassini spacecraft.