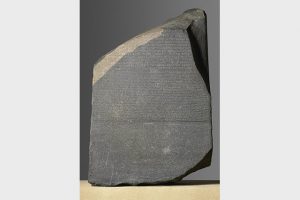

The Rosetta Stone

Egyptologist Richard Parkinson on the object that helped open up the language and textual culture of Ancient E...

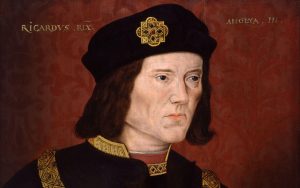

The last member of the house of York to sit upon the throne of England, in his lifetime Richard III seems to have been chiefly famous for his loyalty and good service to his elder brother, King Edward IV. However, after his own government was overthrown by a usurper with French support, but no valid claim to the English crown, Richard became famous chiefly for his heavily blackened reputation. This was by no means a unique event. Rewriting of history has occurred on other occasions in the wake of a violent change of regime.

Richard was the youngest son of the Duke and Duchess of York. At the time of Richard’s birth his father, a cousin of the reigning Lancastrian king, Henry VI, was potentially the heir to Henry’s throne. However, in the year after Richard’s birth, Henry VI’s wife produced a son. This boy may not have been fathered by her mentally disturbed husband, but he was acknowledged as Prince of Wales. The eventual outcome was that the Duke of York decided to put a claim to Parliament that he and his family had a better right to the throne than their Lancastrian cousins. York himself was subsequently killed at the battle of Wakefield. But his eldest son and heir then seized the throne and became King Edward IV.

Edward IV’s Yorkist success was later muddled by his marriage policy. Although attempts were made to negotiate a formal royal marriage for him, Edward himself seems to have preferred relationships with two young and attractive widows. To get what he wanted from them the young king found himself obliged to contract secret marriages with both ladies. The first of the two widows was Lady Eleanor Talbot, daughter of the late Earl of Shrewsbury. Sadly, Eleanor produced no children, either by her first husband, or by the king. Edward therefore embarked on a second relationship with Elizabeth Widville. She had given her first husband two sons. Later she produced numerous children for King Edward. It was therefore her fertility which probably persuaded the young king to accord public recognition to his marriage with Elizabeth, and to have her crowned as his queen.

Elizabeth Widville was a very ambitious woman, and she seems to have been unpopular with other members of the royal family. Moreover, the validity of her marriage seems always to have been disputed. Thus Edward IV’s brother, George, Duke of Clarence, asked that he, rather than the children of Elizabeth Widville, should be recognised as the heir to the throne. This claim led to Clarence’s execution.

When Edward IV died, Elizabeth Widville attempted to initiate an illegal coup. Her aim was to make herself the effective regent for her young son, Edward V, thus ensuring that her family would continue to hold power. In other countries, such as France and Scotland, regency powers for a queen mother were normal practice at that time. But such was not the norm in England.

There, rule on behalf of a child king was traditionally exercised by the senior living male member of the royal family. Thus the rightful ‘protector of the realm’ in 1483 was Edward IV’s surviving brother, Richard, Duke of Gloucester. This point was formally recognised by the ‘three estates of the realm’ (the Lords spiritual and temporal and the Commons who had been summoned to London to form a parliament once a king had been crowned and could open it).

On hearing the news of his elder brother’s death, Richard, Duke of Gloucester acknowledged his nephew, the young Edward V, as the next king. When he reached London and took on the role of protector, Richard continued planning the boy’s coronation. But on Monday 9 June 1483, at one of the preparation meetings, the Bishop of Bath and Wells announced that the coronation could not go ahead, because he himself had celebrated the late king’s marriage to Eleanor Talbot. Thus the Widville marriage was bigamous and all the children born of it were illegitimate.

This news no doubt astonished many people – possibly including Richard Duke of Gloucester. However, it was not treated in a secret way. Richard had the bishop present his evidence to the three estates of the realm. They decided that the bishop was telling the truth. Therefore the so-called ‘Edward V’ had never really been England’s true king. Instead, the three estates offered the crown to his uncle, the lord protector of the realm. That was how the Duke of Gloucester became King Richard III.

After the death of Edward IV, Richard’s right to the role of lord protector of the realm had been supported by two key members of the nobility: the Duke of Buckingham and Lord Hastings, both of whom were of royal descent. However, when Edward V’s right to the throne was questioned by the Bishop of Bath and Wells, Buckingham and Hastings took two different views. Lord Hastings seemed willing to continue to accept Edward V as the legal king. Apparently, he conspired with Bishop Morton in that respect, leading to his ultimate execution for treason. On the other hand the Duke of Buckingham seemed initially to strongly support the contention that the rightful king was his cousin, Richard Duke of Gloucester.

But curiously, following Richard III’s coronation Buckingham changed sides. He then staged a rebellion, the initial aim of which was the restoration of Edward V. Presumably Buckingham hoped that by restoring Edward V to the throne, he himself would become the lord protector. His new aim also suggests that Buckingham had access to the boy in question.

So was he behind an attempt which was made to extract the sons of Edward IV from the Tower of London in July 1483, while Richard III was touring his kingdom? The outcome of that attempt is unknown. But perhaps Buckingham’s actions in respect of the so-called ‘princes in the Tower’ evoked Richard III’s handwritten condemnation of him as ‘the most untrewe creature lyvyng’.

Thanks to the intervention of other plotters (including Bishop Morton and the mother of the future Henry VII) the overall aim of what is known as ‘Buckingham’s Rebellion’ later changed. Instead of pursuing the re-enthronement of Edward V, it began asserting the claim of the future Henry VII. But Buckingham was firmly defeated by Richard’s supporters, and was executed for his treason.

As king of England, Richard III ‘ruled his subjects in his realm full commendably, punishing offenders of his laws, especially extortioners and oppressors of his commons, and cherishing those that were virtuous; by the which discreet guiding he got great thanks of God and love of all his subjects rich and poor’ (John Rous). In a private letter to a friend, Thomas Langton, Bishop of St David’s, wrote ‘I lykyd never the condicions of ony prince so wel as his; God hathe sent hym to us for the wele of all’. Pietro Carmeliano wrote: ‘if we look for truth of souls for wisdom, for loftiness of mind, united with modesty, who stands before our King Richard? What Emperor or Prince can be compared with him in good works or munificence?’

When the news of Richard III’s death reached the city of York, it noted in its records its deep regret at his loss. Yet from then on Richard’s reputation was vilified by the government of Henry VII, who had seized his throne. It is therefore significant that solid evidence exists to show that Henry VII told lies. During his exile in France he had pretended that he was a younger son of King Henry VI as part of his attempt to promote his own feeble claim to the English throne! And after becoming king, Henry’s first legislation included ensuring that Lady Eleanor Talbot and her relationship with Edward IV (the legal basis upon which the throne had been offered to Richard III) ‘maie be for ever out of remembraunce and allso forgott’ (Act of Parliament, November 1485).

Richard III was killed at the battle of Bosworth on 22 August 1485. That was, in a way, rather odd, because Richard had a larger force of supporters than his cousin and enemy, Henry (VII). Also, Richard’s forces were better positioned than those of Henry. But for some reason Richard left his higher ground and led a small cavalry charge down to the marshy land where Henry was. As a result Richard lost his horse and his helmet, and was then surrounded by a small group of enemies, one of whom hit him over the head, stunning him. He was then killed by a heavy blow to the back of his skull.

His body was taken to Leicester and displayed there for three days before being buried. Various late fifteenth- and early sixteenth-century accounts reported different burial places, causing some confusion. In addition a later story (first published in 1612) became popular in Leicester. This alleged that, at the Reformation, Richard’s remains had been dug up and taken to the river Soar. Thus, for four hundred years the whereabouts of King Richard’s body was a matter of dispute.

One of the major problems with Richard III’s reputation as popularly known today is that he figures prominently in plays written about a hundred years after his death by Shakespeare. Unfortunately that playwright’s image of Richard III was based upon a century of political propaganda and the rewriting of history. But Shakespeare does produce some interesting stories! For example, he asserts that Richard III was born prematurely, with teeth, and suffering from deformity. Babies are sometime born prematurely, or come into the world with ‘natal teeth’. But no contemporary documentary evidence exists of either of these in the case of Richard III. In respect of deformity, we now know that Richard had scoliosis. Usually, though, this symptom is not visibly present in a new-born baby, but develops later.

In respect of the alleged ‘natal teeth’, Shakespeare has Edward IV’s younger son, the Duke of York, claiming on stage to have heard that ‘my uncle grew so fast / That he could gnaw a crust at two hours old’. The young boy says that he had heard this from uncle Richard’s nurse. Shakespeare then has Richard’s mother, Cecily Neville, dismiss her little grandson’s assertion by telling him that the nurse in question ‘was dead ere thou wert born’. This conversation is presented by the playwright as having taken place in the summer of 1483. Yet when she herself died, twelve years later, Cecily Neville left the George Inn at Grantham to Richard III’s nurse in her will. Presumably she must therefore have known that the nurse in question was then still alive!

Shakespeare also depicts Richard as a serial killer, alleging that his work in this respect began in 1455, when he killed his mother’s cousin, Edmund Beaufort, Duke of Somerset, at the first battle of St Albans. When that battle took place Richard was two and a half years old! Richard is also accused by Shakespeare of having killed the Lancastrian king, Henry VI, and his alleged son, Edward of Westminster, the Lancastrian Prince of Wales. Yet contemporary letters state clearly that the Prince of Wales died at the battle of Tewkesbury. As for Henry VI, he died in the Tower of London. In spite of assertions which have been made, the date of his death is unclear. But a contemporary account suggests that he died of apoplexy when he heard that his army had been defeated at Tewkesbury.

Shakespeare also suggests that Richard plotted the execution of his brother, the Duke of Clarence. However, contemporary evidence reveals how that execution was planned by Edward IV’s alleged wife, Elizabeth Widville. The Italian friar and diplomat, Domenico Mancini, writing in November 1483, stated that Elizabeth had ‘concluded that her offspring by the king would never come to the throne unless the duke of Clarence were removed; and of this she easily persuaded the king. … [Thus Clarence] was condemned and put to death’. As for Richard, Mancini tells us that he was then ‘overcome with grief for his brother’.

The ghosts of Henry VI, Edward of Westminster and George, Duke of Clarence are among the crowd of ghosts which come to curse the on-stage Richard III on the night before his death in Shakespeare’s play. Other ghosts include his wife, Anne of Warwick, and his nephews, the sons of Edward IV. There is no evidence that Richard had any of those killed.

The later report of how Richard III organised the murder of his nephews was only publicised 19 years after the alleged event, by Richard’s enemy, the usurping king, Henry VII, as part of his attempt to ensure that no more claimants would appear to contest his occupancy of the English throne.

Shakespeare also presents the ghosts of Rivers, Gray, Vaughan, Hastings and Buckingham. Those five men were undoubtedly executed for treason in the reign of Richard III – though not one of them was killed by the king in person. Execution for rebellion and treason was then a normal punishment. Indeed, the only notable point seems to be that Richard III’s government should probably have executed more people for treason – notably Henry VII’s mother, and Bishop Morton. Perhaps then the king would not have been defeated, and his reputation would never have been blackened!

In 2004 I was commissioned by the BBC to investigate the ‘body in the river’ story. I decided it was a myth, because a private letter written in 1611 mentioned seeing a stone pillar commemorating the king in a Leicester garden. At about the same time I also found a source at the National Archives which confirmed that in the 1490s Richard’s bones lay buried in the Franciscan Priory church in Leicester. I also discovered Richard III’s mtDNA sequence. All this information, together with my prediction of the location of the lost church of the Franciscan Priory, led to my collaboration with Philippa Langley; to the foundation of the LOOKING FOR RICHARD PROJECT; and eventually (with the support of the Richard III Society) to the commissioning of archaeologists of the University of Leicester to excavate the predicted site. There – despite Leicester pessimism – the king’s bones were found on the very first day of the dig – which also happened to be the anniversary of Richard III’s burial in 1485! I subsequently carried them from the car park – having placed a modern copy of Richard’s royal standard over the cardboard box.

Since I introduced science into the search for Richard III by the mtDNA discovery in 2004, other scientific issues have arisen, some of which are still unresolved. In 2006 I also published the fact that the living Somerset family offered potential sources to reveal Richard III’s Y-chromosome. But although the mtDNA of the bones found in Leicester matched the mtDNA sequence which I discovered in 2004, the Y chromosome of the Leicester bones proved not to match that of the living Somersets. As the living Somersets themselves revealed two different Y chromosomes within their ‘family’, it seems probable that there has been recent illegitimacy in their line of descent. However, some writers have suggested that Richard III’s grandfather may have been illegitimate. This issue cannot be resolved until more evidence for the medieval royal Y chromosome is found, and I am working on that now.

Another scientific issue which I recently published relates to hypodontia. It had previously been argued that the congenital absence of teeth shows that the two skulls found with bones at the Tower of London in 1674, and reburied at Westminster Abbey as the sons of Edward IV, were closely related to one another. It was also argued that since Anne Mowbray – child bride of the younger son, and second cousin of both the ‘princes in the Tower’ – also had hypodontia, that proved that the bones found at the Tower really were the remains of the ‘princes’. However, in 1996 I revealed that Anne Mowbray may have inherited her missing teeth in her maternal Talbot line of ancestry, because bones found at the Carmelite priory in Norwich, which may be those of Anne’s aunt, Lady Eleanor Talbot, show the same feature. More recently I drew attention to the fact that the skull of Richard III – a much closer relative of the two ‘princes’ – exhibits no hypodontia. Therefore what was claimed to be scientific evidence for the identity of the Tower bones has now been shown to be questionable.

Of course, the fate of Edward IV’s sons – Richard III’s nephews – is still a major question. The LOOKING FOR RICHARD PROJECT always had two aims – to find Richard III’s lost remains, and to reveal the truth about his story. Since we found his remains in 2012, some of us have continued working on other related issues. Perhaps the most important of these is finding out what really became of his nephews – the sons of Edward IV.

Egyptologist Richard Parkinson on the object that helped open up the language and textual culture of Ancient E...

Historian John Ashdown-Hill on one of the most controversial figures in English history, Shakespeare's dark im...

Historian of science Loren R. Graham on the mistakes Russian leaders make, intellectual property and risky inv...