Temporal discounting

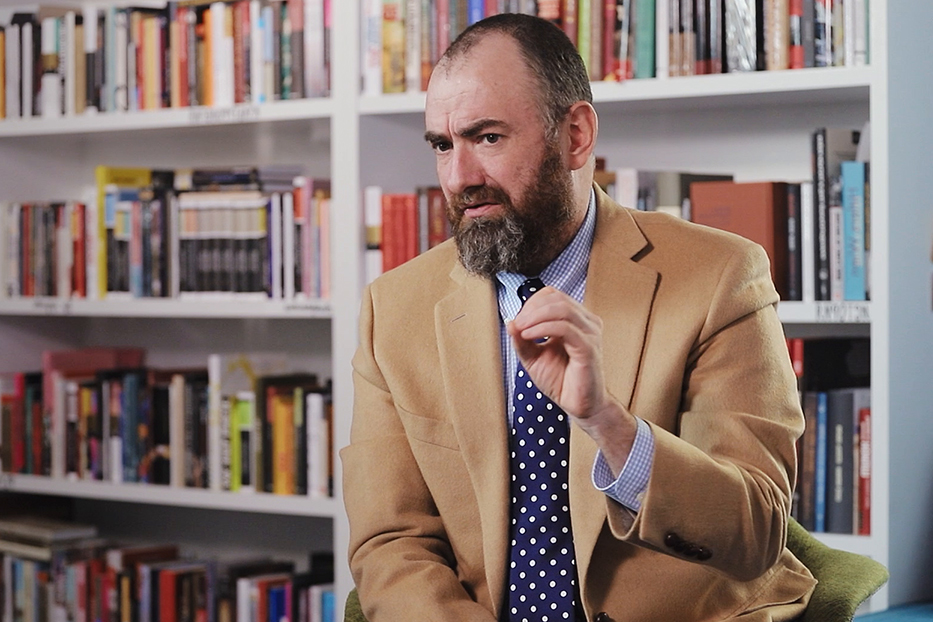

Neuroscientist Samuel McClure on why we violate our best intentions, ‘dual selves model’, and pathways in our brain that process decisions

videos | October 28, 2015

What are the two systems in the brain responsible for our motivation? What methods are used today to compare the motivational and more deliberative brain systems in action? Can we predict when people are going to be impatient and when they will make more weighted decisions? These and other questions are answered by Samuel McClure, Assistant Professor, Department of Psychology, Stanford University.

One way to think about this question that’s been around in psychology, philosophy, economics for a long time is by positing that we actually have many different motivations, that our behavior is driven by many independent considerations, and we have different ways of evaluating the world. Because we have these different styles of evaluating the world, sometimes these can conflict. This is the classic take on how time discounting works. Which is, that we have an ability to formulate the long-term plans in abstract fashion and generate best wishes and best desires, but we also have this ability to evaluate the world, see something as a very attractive and desirable good, generate emotions and high motivation to achieve it, but it seems fundamentally different. One is very deliberative in nature where you think, and plan and reason, the other is driven by the here and now, the presence of something that seems very appetitive and satisfying. So this has been very long idea that is called the dual selves model of time discounting and preferences. There is been a lot of interest for a hundred of years in this notion. It’s just it’s been hard to test.

Neuroscience has been trying to test this and it turns out that there are systems in the brain, networks of brain areas, that interact to control behavior that roughly correspond to this idea of a more affective and a more deliberative kind of system. So the affective system seems to correspond to this basic older evolutionary system that releases this neurotransmitter dopamine. So the dopamine system – we associate with emotions. If you activate the dopamine system, there is positive arousal and positive emotions that correspond to that. It has basic motivational properties, so this system is strongly associated with a sense of motivation for seeking whatever is available in your environment. And it functions in this relatively automatic fashion, where dopamine is released – it signals the value of the things in your world through direct association. So when you see something in the world, it signals the dopamine system in this automatic fashion to release the amount of dopamine that corresponds to how valuable it really is.

We also know there is a another system in the brain dependent on something completely different which is the prefrontal cortex. The prefrontal cortex – we know largely about because of lesions. If you have a stroke, that causes damage to your prefrontal cortex. Then you selectively lose the ability to formulate abstract goals and guide your behavior on the basis of those goals. One of the consequences of damage to this region is called ‘environmental dependency syndrome’. It’s really a fascinating set of problems. What characterizes it is that your behavior becomes dependent on what’s directly in front of you and these patients have the inability to guide their behavior more reflexively based on abstract goals. …This ability to abstractly plan, structure your behavior in accord with abstract goals really corresponds to this more deliberative kind of system.