Voyager and the Heliopause Crossing

Director of research at LATMOS, Jean-Loup Bertaux, on the current locations of Voyager One and Two, the Heliop...

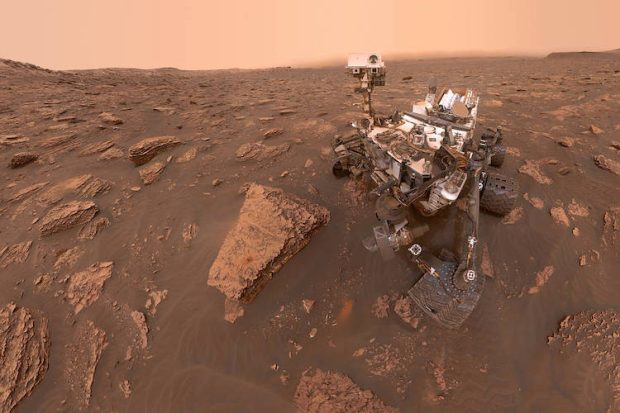

We have many images from Mars but not all of them are adequate to answer this question since some are white-balanced to provide better contrast for human sight. Fortunately enough, there are some interesting studies in the literature dealing with the chromaticity of the Martian sky and providing sound physical reasons for its aspect.

Using the Panoramic Camera (Pancam instrument) onboard Mars Exploration Rovers Spirit and Opportunity, Bell III and collaborators determined the color of the sky from radiometrically calibrated images. This means that image values have been transformed into physical quantities (i.e., flux or radiance) by taking into account the spectral response of the camera and filters, the incoming solar flux at Mars’ surface, and other factors. Spirit and Opportunity reported “bluish-black” or “black” skies in dust-free atmospheres. However, most of the time, Mars’ atmosphere is loaded with lots of dust, so this is not a common aspect of the sky.

The color of the sky depends on how the solar radiation is scattered out of the direct light beam illuminating the ground and also how the scattered and direct beams are absorbed by molecules and particles in the atmosphere. For example, if there were no atmosphere, as it is on the Moon, you would find a dark sky and a yellow Sun. On Earth, the blue sky color is produced by the so-called Rayleigh scattering by which the molecules, with a radius, is lesser than the wavelength of the radiation (approximately 1/10), are more efficient in scattering light at shorter wavelengths, the scattering cross section is inversely proportional to the power of four of wavelength.

Although Mars’ atmosphere is much thinner and molecular scattering is thus less efficient. In principle, the Martian dust could have played the role of our terrestrial air molecules, scattering shorter wavelengths more efficiently and thus ultimately producing blue skies and red sunsets as on Earth. It might have been so if such particles had acted as perfect scatterers with no absorption. However, Martian dust is rich in blue-absorbing iron oxides that produce just the opposite effect by simply removing the shortest wavelengths from the radiation beam.

Rovers reported “dark yellowish brown” skies (i.e., “butterscotch”) for the common situations in which plenty of dust remains suspended in the atmosphere of Mars, but since the dust could contribute to making the sky be perceived bluer (by means of scattering) or redder (by means of absorption), a more careful explanation is required here. Kurt Ehlers and his collaborators produced an enlightening study that anyone familiar with atmospheric optics will appreciate. They considered the complex effect of micron-sized, blue-absorbing, forward-scattering dust and demonstrated that reddening is slightly more efficient, thus leading to “butterscotch” skies for “dusty situations”. Moreover, the longer wavelengths (red) and the shorter wavelengths (blue) are scattered in very different patterns, producing some other interesting effects, such as the blue glow that follows the Sun on its path over the Martian sky.

According to this study, there seems to be a butterscotch sky and the Sun in a bluish glow, particularly noticeable during the sunsets on Mars. But things are more complex with human perception.

Since Mars is roughly 1.5 astronomical units from the Sun, the amount of light on the surface is about half that on our planet. Under low illumination conditions, our eyes shift sensitivity towards blue because we change from using color-sensitive “cone” cells to color-blind “rod” cells. This is known as the Purkinje effect. Hence, the first astronaut to land on Mars would probably describe its sky as even bluer than one might expect.

Director of research at LATMOS, Jean-Loup Bertaux, on the current locations of Voyager One and Two, the Heliop...

Physicist Joshua Winn on the difficulties of exoplanetary research, how researchers managed to get lucky with ...

Theoretical Physicist Ugo Moschella on the history of the Universe, symmetry breaking and the Electroweak theo...