What Will Happen If a Giant Meteorite Hits the Ear...

Will it destroy everything?

In September PLOS ONE published an article called ‘Coordinated Feeding Behavior in Trichoplax, an Animal without Synapses.’ featuring the behavior of one of the simplest multicellular organisms – Trichoplax. We asked one of the authors, Dr Carolyn Smith, to comment on this study.

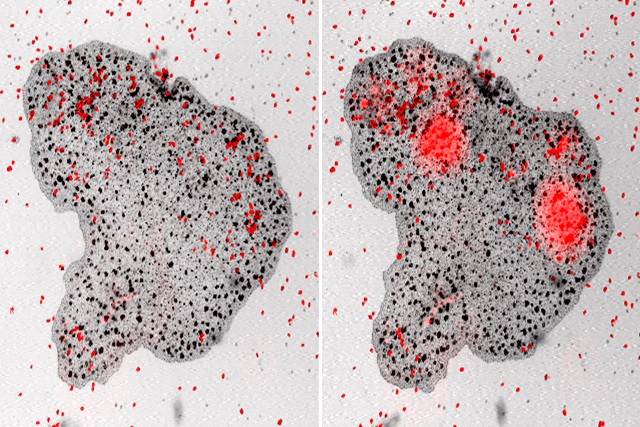

We used a confocal microscope to watch Trixoplax feeding on algae on a microscope slide to learn how an animal with no nerves, muscles or stomach could find food and eat it. The lower surface of the animal has numerous cilia (tiny whip-like appendages) that beat asynchronously to propel it along a surface. The animal’s movements appeared random but when it encountered a clump of algae, its cilia stopped beating and it came to a halt. Then secretory cells on the lower surface secreted large granules that lysed the algae, causing them to burst and release their contents, including chlorphyll and phycoerythrin, which are fluorescent and therefore visible with a fluorescence microscope. We were amazed to discover that only secretory cells in close vicinity to algae secreted granules because this meant that not only could the animal sense where the algae wereб but also accurately target secretions onto them. The animal then made churning movements while the contents of the algae were digested, presumably by pinocytosis (uptake in vesicles). Once the material released by the algae had largely disappeared, the cilia starting beating, and the animal crawled away. Even though placozoans are morphologically simple, their mode of feeding is far from simple, marshaling precise control of movements and targeted discharge of digestive enzymes to accomplish digestion externally. Indeed, their behavior suggests the presence of a primitive nervous system.

Trixoplax adhaerens is a tiny, coin-shaped animal found in temperate and subtropical oceans where it glides upon surfaces feeding on algae. It is among the simplest free-living animals known, having only six cell types and lacking muscles and a recognizable nervous system. Trichoplax is sufficiently different from other animals to be placed in a phylum of its own (Placozoa), and remains the sole named member of this phylum, although genetically distinct subtypes have been identified. Placozoa, along with Porifera (sponges) and Ctenophora (comb jellies), are thought to have appeared during the Precambrian, more than 550 million years ago, well before trilobites.

Although Trichoplax is unique among extant animals in feeding by external digestion, this mode of feeding is thought to have been more common among simple Precambrian animals that, like Trichoplax, lacked a stomach and synapses. Our goal now is to achieve a detailed mechanistic understanding of how Trichoplax senses algae and coordinates the activity of the different cell types that participate in the feeding behavior. This information may provide a glimpse into the lifestyles of the ancestors of modern animals as well as insight into the origins of nervous systems.

Will it destroy everything?

Historian Richard Bourke on political community, history of political philosophy, and the modern struggle over...

Biomedical Engineer Thomas Heldt on preventive patient care, patterns of disease progression, and quantifying ...