Social Cognition

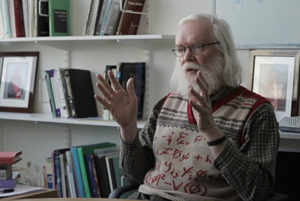

Neuropsychologist Chris Frith on the experiments with biological motion, emotion recognition, and open questio...

The video is a part of the project British Scientists produced in collaboration between Serious Science and the British Council.

Microbiome is a newly discovered organ in the body, and it’s also the name given to the community of all the microbes that live in our body. It’s a collective word and these microbes are bacteria, archaea, the viruses, the fungi, the protists. Together they actually weigh about 2kg. So this organ, this virtual virtual organ, most of them live in the lower part of the intestines called the colon, and they’re the same size and weight as the liver. So they are a really important part of our body, which we thought was rather boring until very recently. It turns out there are 100 trillion microbes inside us, which is roughly 10 times the number of cells in our body. So, you could say that we are 90% alien and only 10% human.

Rather than just being boring creatures that live in the dark waiting for food, they are actually really crucial to how we digest our food. We have hundreds of enzymes and chemicals that break down our fiber much more than we do in our human cells. We’ve evolved with them over millions of years, so we actually share 40% of our genes with them. But they have 200 times more genes than we do. All of them like little factories producing proteins, chemicals, enzymes, many of which we still don’t know what they do. But we do know they also have a key role in maintaining our immune system. Because when these microbes feed off fiber that gets down into our guts, they will produce short-chain fatty acids, little chemical signals, very small, that actually will influence our immune cells and suppress the immune system. So stop it overreacting, stop us getting allergy, stop us getting autoimmune disease. At the same time they also produce about a quarter of our hormones and our vitamins. And these important B-vitamins and even brain chemicals like serotonin, you may have heard of, that is really important for our chemical signaling in the brain and making us feeling happy and being sad.

It’s these microbes that are doing this all the time, these little chemical factories that are absolutely crucial. That’s why this new study of microbiome is so exciting, because we’re realizing that not only they’re doing this, that also we’re all very unique: we’ll have a unique set of microbes, you will have just one set of microbes that only one in twenty thousand people will have. And then you share about 20% of our microbes with each other on average. So understanding these individual differences in our microbes explains why we react differently to foods, why one person can eat a potato and gain weight, another person might lose weight, why someone might get a food reaction to something. These are all really important and may explain also why we react to drugs and medications differently, when some people get hangovers and others don’t, why some people get vitamin deficiencies more quickly than others. So the microbiome is explaining much of the things that we’ve been puzzled by. Particularly in nutrition as well. So by understanding the microbiome, we learn a lot about science and a lot about our individuality.

The range is amazing. What we’re realizing is that if you separate sick people and healthy people, you always see some consistent signs of healthiness, which is a diverse microbiome. And if you look at sick people, whether they are overweight, or they have diabetes or some common disease, they have much less diversity. It appears that this is really crucial for us – having enough of these beneficial microbes to keep our bodies healthy. We’re just beginning to understand the links about this and how it interacts with most of the diseases we find. We’ve been able to actually, through animal experiments using sterile mice, work out how you can actually transmit some of these traits from humans to mice and from mice to mice. So, potentially many of these diseases and conditions like obesity can actually be infectious by changing our microbes.

The microbiome is now being used a wide variety of areas: it’s been used in cancer to help people respond to chemotherapy by either using probiotics to improve the community, or actually by giving people back – autotransplanting – their microbes before the chemotherapy, so that they don’t get sick when they get antibiotics. It’s also been used in autoimmune diseases to help people respond to immune therapies. We understand that’s also important for the skin, it can help people with psoriasis. There are even lots of non-medical uses of the microbiome as well: people are mining these genes in the microbes, there might be useful ways is creating new fuels or new biological drugs. So, in a way there’s an infinite number of possibilities that are available to us from this new world that’s opened up inside us.

In terms of the microbiome now, we just look at the tip of the iceberg. We know the detailed functions of only a very small percentage of all the microbes out there. But we are seeing consistent ones that are related to two human conditions. These same microbes do keep recurring. When we looked in our twin studies here in the department at King’s College, we were testing the microbes of all the twins that came through. So, we looked at about 4,000 stool samples from

the twins, we extracted the DNA, we worked with colleagues from Cornell University, we analyzed the results and we compared the identical and non-identical twins for their microbes. It turned out there were some greater similarities in the identical twins compared to the non-identical twins. So, it seems that some of the microbes that live inside us are there for genetic reasons. They like us more than other people. We don’t know why, and it could be a two-way reaction: that we like them and they like us and that’s why we coexist.

We are looking at our lifestyles and particularly trying to change our views on antibiotics and pesticides and reverse some of the mistakes we’ve made in the past, because generally our diversity of microbes in every country tested has gone down in the last 40 years. In the era before we had processed foods, before we had antibiotics, before we had these sterile caesarian section births we were much better off and studies in Africa from tribes that still live like we used to have much healthier microbes. We’ve got a long way to get back to our healthy roots.

The big question is – how do we get back some of the microbes we’ve lost? When we compare ourselves to the hunter-gatherers in, say, Tanzania we’ve lost about 40% of our microbes. They have many species that we no longer have in the West. One way is to start reintroducing them, like early farming. We could start farming them up and see if we can introduce them back into humans, get them back as part of our chain. We don’t know if that’s going to be successful or not, but we know that very often rather than having zero amount inside us, we may have very small amounts inside us of some beneficial ones that we can grow up. We use prebiotics for that, ‘prebiotic’ is a term like a fertilize of your microbes. So by giving them more to eat and working out which microbes like to eat which food we can start to stimulate them and get them to grow. It could be a combination of giving some of these seeds from these beneficial microbes that are no longer with us, which’d we call probiotics. Because probiotic is alive microbe that you might think of normally in yogurt, or kefir, or some sauerkraut, fermented foods having those plus a high-fiber diet that’s created to try and boost these numbers of these rare microbes.

I think, we are at the very early stages of understanding this. But we do know that some foods you can improve microbes quite a lot. So I think, it’s a mixture, but also it’s changing our lifestyles, it’s saying: “You know we have to stop using antibiotics indiscriminately, we have to stop unnecessary cesarean sections, we have to stop our indoor living, we have to reconnect with nature in order to get full benefit of microbes”. Having a dog, for example, is healthy for your microbes and so we should all be stroking dogs and going to farms. And things much more interesting: not cats, just dogs that seems to be so. A lifestyle for our kids, it’s different from the one we’ve been brought up. We let them get dirty, get them playing outdoors, get them eating more vegetables, less processed foods and go back to nature.

Neuropsychologist Chris Frith on the experiments with biological motion, emotion recognition, and open questio...

Physicist John Ellis on what the Higgs boson is and the history of its discovery

Biologist Tim Spector on how microbes determine obesity, the best kind of diet, and the reasons to refrain fro...