Education in the Middle Ages

Historian Peter Jones on monastic education, cathedral schools and apprenticeship in the Middle Ages

There’s a wonderful text known as the Colloquium of Ælfric Bata, Bata meaning the “chubby”, so Ælfric “the Fat”. This is a whole series of stories, dialogs which are designed to help teach young monks Latin, and they are designed to appeal to the average 12-year-old boy, so that they’re full of toilet humour, they are full of jokes, they are full of lots of slightly silly things, but they’re also very, very revealing because they show us a side of how a society worked and how people got on in monasteries that you tend not to see. In the course of one of these stories we hear about how one monk is writing a book, and one of the others then comes up to him and says: “I want to buy your book”, and they launch into a little exchange about how they might do this, and the one who wants to buy the book says: “I could pay you in” and then he reams off about 20 different things “I could pay you in sheep, goats, cow, beans, hay…” – all sorts of things, which is clearly meant in part to teach you vocabulary. But it also gets at the point that they understand money and payment in this very, very loose broadway. It can mean lots of things, but then the one who’s got the book to sell says: “What I want is for you to pay me silver or coins”, because, as he puts it, “he who has silver can get anything he wants”. And this is crucial because they already see what the attraction isn’t money, they see that it’s a kind of proxy for our trust in one another that if we put our faith as a collective group into the money, then everyone will trust it and accept it as a store of value for other things.

All of this is moving into the realm of coinage, all of this is turning into silver pennies, which was a standard denomination in England at this stage, and being utilized on a very, very broad level, much broader than it had been for quite some time before then. You start to see in this period, for instance, in the manuscript that’s written in Canterbury in the early 11th century, which is an Old English rendition of the Gospels, you start to see when they talk just about paying things in the Gospels, they don’t mention money, but when they draw pictures to accompany this in the manuscript, they do use money. It’s starting to become the way in which people think exchange works as standard in many situations. So the money is coming in being used by all these people through all these different things, including by peasants who need to pay their landlord and who then need to go and buy and sell in the market to get the money to pay their landlord. It’s also being used more widely in towns, it’s being used for all sorts of people who will not have a regular contact to each other. In the more complex society, like a place such as London, or York, or Lincoln, lots of people coming and going all the time.

You can follow this process in a lot of detail by looking at records of various kinds, not just Domesday Book, which is the most famous and dramatic of these, a survey of the whole Kingdom, who owns what, and crucially how much they can expect to get from it, measured in terms of pounds, shillings, and pennies, silver coins and multiples of these silver coins. Beyond Domesday Book, there are earlier documents which show the background from which it springs. These, again, are predicated on an interest in trying to squeeze resources out of estates and people who live on those estates, very often in monetary form. There’s a great example of this from a monastery in Cambridgeshire, the East of England, called Ely, and from there, probably in the ten twenties, ten thirties, there was a series of short records put together, which show you how the monks were running their estates, scattered all over the East of England. When they get on to a number of these, they speak very explicitly in terms of paying people silver or even gold, they speak in terms of how much money is going to be used for buying land, buying these resources, buying that resource, how much various tenants are going to be bringing into them. They are thinking about all sorts of different resources, but very prominent among those is coined money, and you have proxies for coined money, too, things like what they call ‘hired man, heeded man’ in Old English, a man who will be working for pay. The idea of using a silver coin, using cash is penetrated quite thoroughly into medieval English society, already by the 11th century, and just goes from strength to strength as one goes into the 12th and 13th centuries, but it’s absolutely transformational in the 11th. It’s that in the increased supply, which prompts this pressure on people to use it more. It’s not necessarily something that your peasants want to do, but it’s something that they have to do.

There are important questions over exactly how the finds that we see in the Baltic actually did get there and operated once they arrived, but there’s got to be some sort of connection. In some ways, more important for understanding what’s going on within England are finds that are made from their books, of course, that’s within the home territory that they were thinking of first and foremost when they made these things. You have other hoards, groups of coins that were put together and then hidden in the ground. Those were immensely valuable for telling you about what was available at one time, how people handled larger sums of money. But you also have coming on line in more recent times what we know as single-finds, and these are coins which were probably lost on an individual basis and have been found and dug up by people going up with metal detectors in the last few decades. And these people go all over fields, all over the countryside and they find these coins and log them. And these are crucial because it’s thought that each one was lost as a separate case, they lost one by one. People don’t choose which to lose. That means that they provide you with the cross-section of what’s actually being used, a more representative vision of the monetary economy than the hoards which are picked, chosen, selected in order to form sort of a coherent parcel of money.

The question I would like to know the answer to in relation to the 11th century money is where is the silver coming from, because they’re clearly making a vast amount of coins and they’re clearly sending a vast amount of money across of the Baltic, but what we’re not sure of is how much of that represents recycle English money, how much of that represents money that’s coming in fresh from Germany, how much of it had been other objects beforehand, and you can try to solve this by analyzing the silver on a molecular level finding out what the trace elements are alongside silver, but that can only take you so far. What we really need is a time machine to be able to go back and see what was actually going on, how people were actually picking and choosing their supplies of bullion, and turning them into cash.

Historian Peter Jones on monastic education, cathedral schools and apprenticeship in the Middle Ages

Historian Alessandro Scafi on the garden of Eden, Augustin's concept of creation, and the emergence of the ter...

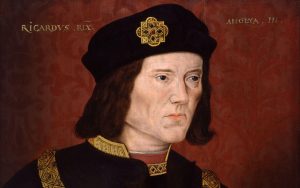

Historian John Ashdown-Hill on one of the most controversial figures in English history, Shakespeare's dark im...