Free Will and Moral Responsibility

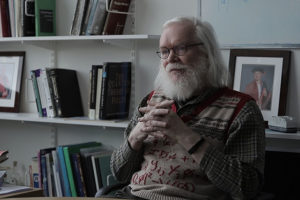

Philosopher Derk Pereboom on compatibilism, causal determination, and Spinoza

The video is a part of the project British Scientists produced in collaboration between Serious Science and the British Council.

Autism is a neurodevelopmental disorder. That means it is a brain disorder. It has a genetic origin which is still quite unknown, it starts incredibly early in life and affects the brain and the mind, it affects it seriously. The condition that is known as autism is a condition that makes it almost impossible for the person affected to lead an ordinary normal life. They need a lot of help, a lot of support. Autism was always with us clearly, but it has not been named until the 1940-s And it was quite independently that it was identified by two people: one in Austria, Hans Asperger, who described a series of cases that he had come across. He found something in common with these cases that he thought pointed to a particular kind of what he called ‘psychopathy’.

Actually, it does not mean what we now mean by psychopathy. He meant it was not a debilitating disease. He meant it was something like a personality feature. These were people who did not fit into groups, who were loners, who were strange, and who also sometimes had special talents. But he described these first cases in such a way that we could see that each individual was very different. So there is a whole range of individual differences.

And at the same time in America Leo Kanner, psychiatrist, also became aware of children in his practice who, he thought, had something in common. And it was exactly the same that Hans Asperger identified. It was an inability to relate to other people. They had a reasonably good ability to relate to objects and things in the world. But that is different from people. In fact, Kanner described very vividly a child who was in his consulting room who would pay more attention to the filing cabinet than to him. So these children did not seem to be especially affected by normal human interaction and communication. Kanner too decided that in his cases he often noticed some kind of special what he called ‘islet of intelligence’. One example: a child who would hardly speak in a spontaneous way and really engage in conversation, but had a fantastic memory and could recite things be heart that many people would just not be able to remember like that.

So we have these descriptions in the 1940s and this was of course in the middle of World War II. So at first, I think, not much notice was given to these cases. But then, very soon thereafter, people began to see such cases everywhere. At first it only a few and it was thought to be very rare. It was among the people who were in hospitals, who were considered mentally deficient but had not got a special label. And it was quite clear that a very large number of them could be identified afterwards as autistic. It took a long time until people realized that it was not only children that had autism but when children grew up and became adults, they were still autistic.

So a neurodevelopmental disorder like autism is for life. However, the behavioral signs change with age. The behavior cannot be listed in a catalog so that you could say “you need to show, for example, a very good memory and inability to distinguish between a person and a piece of furniture”. It is not possible to do that because the behavior differs according to age and ability, and all sorts of other things. And yet, it is the only way to diagnose the autism. There is no biological test for it as yet. We know it is a biologically caused disorder, but we have no idea of how to capture this. We have some hopes that we can see some kind of biomarker in the brain. That is possibly not the structure so much of the brain but the function of the brain, the way that different regions in the brain connect with each other. That is probably where we will eventually find the first kind of biomarker.

But at the moment, all we have is behavioral signs and the clinician’s’ judgment and intuition. And here is something interesting. The experienced clinician can identify autism very quickly and agree with people around the world. And it is interesting to think why we can do this when it is, in fact, such a very heterogeneous disorder, so different in different individuals.

I think it is the key to explaining what is different in people with autism. And a key is what we might call reciprocal communication. So when we communicate with each other mostly in language, but it does not have to words, it could be signs, it could be touch, it could be some other things. When we do this normally it is a very fluid unconscious turn-taking. We take into account what the other person already knows, does not know, we like to tell something new and interesting, not the same boring thing all over again. And with the autistic person, this seems to be missing. But when you attempt to have a conversation with an autistic person this just does not happen. There is not this turn=taking and this reciprocal interplay. And this is why it often happens that an autistic person will tell you the same thing over and over again? things that you know already, things that have to do with their own special interests. And it is not easy for them to see when other people might just wish to change the topic, might ask something else. That is just a very strong example of what is missing in the social interaction in autism. That is critical.

You might think it is not such a serious matter, but it turns out to be incredibly serious because, given that it already starts very early in infancy, you can imagine that if you have no reciprocal relationship to other people, it would be very difficult to learn things by teaching. You might just not be attuned to picking up what is important, what is interesting. You go your own way, you behave as if you were alone in the world. And in fact that is where the name autism comes from.

Autism comes from the Greek autós (αὐτός) which means ‘self’. So just the self as if nothing else counted. So it is very serious. However it is true that during life, during the lifespan, children, as they grow up, do learn slowly and with effort and some of them can adapt to society, not in this millisecond to millisecond tracking of other people’s beliefs and feelings that we need to do when we interact, but in a slower way. So they can interact sometimes very well when it is at a distance, when they can use e-mail, because they can then think about the answer, they can study what you said. So this is a different form of communication, that they can achieve. Not all of them, because a quite large proportion of autistic individuals probably half, possibly more than half, have additional neurological problems which include very often mental retardation or learning disability, which manifests itself as not doing very well on IQ tests, on tasks that you give them. It means also probably that their language is rather limited, less fluent than it might be. They quite often have epilepsy as a condition that also needs to be treated on its own right. And that can produce great difficulties.

Because they do not have this easy turn-taking and alignment to other people, they often behave very badly. That is how we see it. The do not fit in, they seem to be misbehaving a lot of the time. They do things that social pressures in our normal life would tell us ‘no, this is not the thing to do now’. And they might be offensive to other people because they just do not particularly regard them. We still believe there is some truth to Kanner’s assessment that they cannot tell such easily the difference between how to relate to people and how to relate to objects in space.

We now talk about a spectrum of autism, which means that there are amazing differences between different individuals. So you can have one child who does not speak at all, who has severe learning disabilities who is really very alone with himself. And on the other extreme, you have a person who is highly intelligent, has some very specialist interest, possibly a great talent, maybe is a chess master, but does not do very much else and still does not fit into society in the normal way. And in the middle, you can have all sorts of shades in between of people who can manage reasonably well with support, with help, and others who really need a lot of help and need to be looked after all the time.

So the main questions at the moment that we all want to know is – what causes autism. And we do now agree that the causes are genetic factors. And it is not as you could find one, or two, or three genes. It is like hundreds of genes, that are sort of involved and interact with each other and lead to different forms of autism, which still in the end have the effect that is a kind of bottleneck. So far as the brain is concerned in the large scale there are certain regions in the brain that are not terribly well-connected, whatever the initial causes were. And this is very interesting, we get probably many different genetic causes but possibly fewer manifestations of these different causes in the brain. And then again we get many different manifestations in behavior. So that is why it is a very interesting disorder to consider. And what we have to do in the future is to see what happens in the brain, what actually is this thing that pulls these things together from all these different biological causes and pulls these things together from different behaviors. We are not quite sure about that, but there are some ideas. Of course, we do want to know what all these possible genetic risk factors are. So people are collecting cases where they can study particular genetic causes, but it is almost like every single case has a different genetic basis. So it is adding up all the time, and I think we can probably now explain about 20% of all causes of autism via nongenetic factors, even though they are all different, all variable. And the rest we expect we will know in the future.

Philosopher Derk Pereboom on compatibilism, causal determination, and Spinoza

MIT Human Stem Cell Lab. Director Maya Mitalipova on age-related diseases, stem cells, and new ways to model n...

Physicist John Ellis on discovery of dark matter, ways to look for it and what dark matter particles might be