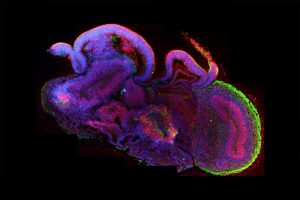

Brain Organoids

Neurobiologist Madeline Lancaster on brain development, cerebral organoids and how close they are to actually ...

Many people, at some point in their lives, experience sadness and possibly even feel deeply depressed. However, when we talk about it in terms of the medical condition, major depressive disorder, it actually has strict criteria that go beyond just the feelings of sadness. Major depressive disorder is a condition that affects aspects of emotion, cognition, and behavior that result in a significant negative impact on a person’s functioning and well-being. Diagnosing major depressive disorder is actually tricky since there is no simple laboratory test or questionnaire that can be used to make the diagnosis. In fact, major depressive disorder is what we call a diagnosis of exclusion, which means that in order to really diagnose someone with the disorder, you have to be able to rule out the other possibilities that could be underlying the symptoms. You have to make sure that it is not due to any other type of medical disorder or even if it is substance use or medication side effects. At present major depressive disorder remains a descriptive diagnosis that simply labels the conglomeration of core symptoms that affect emotion, cognition, and behavior, but it does not inform us at all about the processes or neurobiology related to the disorder.

Depression is something that has been documented in human history for over a thousand years. There are reports of melancholia dating back to the time of ancient Greeks. Its history has evolved over time, ranging from beliefs that it was caused by supernatural demonic possession to the time where it was seen as a personal weakness, evolving through the era of psychoanalysis to the modern era where we believe that it is an actual medical illness related to altered physiologic processes and brain function.

Problems with emotional regulation are the symptom most people associate with depression. This is most commonly experienced as feelings of sadness, but there are also people that are not necessarily feeling sad but experience anhedonia, which is the inability to experience pleasure or joy. The inability to experience joy or reward is believed to be associated at some level with another common symptom of demotivation or difficulty in initiating activities. Other people could also experience feelings of guilt, periods of irritability, and problems with anger related to depression.

In addition, there are also core cognitive symptoms associated with the diagnosis. Individuals suffering from a major depressive disorder commonly have problems with concentration. Many people report difficulties maintaining focus and the ability to sustain concentration on tasks. Others have difficulty shifting from one thought process to another. These people can get caught in ruminative thought patterns that are frequently associated with feelings of failure, worthlessness, and hopelessness. Many depressed individuals also report significant problems with indecisiveness and the inability to make even simple decisions. Most concerning, depressed individuals could also be caught in a cycle of morbid thoughts and become preoccupied with thoughts of death or even suicide. These are all symptoms believed to be reflecting some problems in regulating cognition.

The last group of symptoms is what we typically call behavioral symptoms. Here we commonly talk about vegetative symptoms, such as changes in appetite, sleep, and energy. Classic melancholic depression is characterized by patients having a significant reduction in their appetite, problems falling and remaining asleep, and a slowing of physical actions. However, with other types of depression, including atypical depression, you may actually see opposite effects on appetite and arousal with overeating and increased time spent sleeping.

In most cases, a depressed individual will experience some disturbance in all three aspects of emotion, cognition, and behavior. However, the relative extent and severity of the unique symptoms vary between individuals.

Although there have been great efforts to understand the causes of depression, we really do not have a clear understanding of the genesis of the disorder. There have been evolving theories over the years. At present, the two factors most commonly identified as related to depression are genetics and life stresses. There is clear evidence of the genetic relevance to depression. The disorder is more common among individuals that have a first-degree relative with depression or another mood disorder, suggesting that genetics contributes to a person’s chances of developing depression. However, we also understand that life stresses, or perceived life stress, could have a major impact on the appearance of depression. Interestingly, in some ways reflecting earlier psychoanalytic theories, evidence now suggests that it is not only current stressors but also exposure to life stresses at early points in life that may place an individual at risk. Attempts to understand how psychological stress could actually play a role in changing brain structure and function and how these changes are related to the development of the disorder is one of the most exciting areas of research being pursued at this time.

We frequently talk about depression or major depressive disorder as it is a single illness with a common underlying cause and biology. However, the large majority of clinicians and scientists in the field would not agree with this assumption. There is little evidence to suggest that major depressive disorder is a single illness. We must remember that major depressive disorder remains a diagnosis of exclusion under the current diagnostic system that is made when we cannot find another good explanation for an individual’s specific set of symptoms. By definition, this means that we do not know what is causing it. There are likely many different pathophysiological mechanisms that could be related to this disorder and could be underlying the development of the disorder.

Depression is a very common disorder. Depending on what level of diagnostic reliability people are willing to accept, some studies can show that up to 17% of the population at some point in their lives experience a major depressive episode for women, which can be 20% or even higher in some studies. As the disorder is so common, with one in four or five women experiencing major depressive episodes at some point in their lives, it makes it difficult to evaluate the true increase of the risk of having depression if you have a first-degree relative depression. Having a first-degree relative with the disorder does place you at a higher risk, but it does not mean you are destined to experience depression.

Depression has been much more frequently diagnosed in the last few decades. However, it is difficult to determine if it is truly more prevalent now or if it is just more frequently diagnosed based on the increased attention that is being paid to this disorder. There is some evidence to suggest that there may actually be an increase in the rates over the past few decades, but it is not very clear because it is hard to collect data on previous generations, where it was not really looked for as much.

Diagnosing depression is much more difficult than most people would consider. If we use what is still considered the standard diagnostic system, which would currently be the DSM-5, it is really a list of symptoms and signs, and if you have a certain number of them, you would be considered to meet those first-level criteria, as long as one of the prominent symptoms is having some change in your mood or emotion. The second level criterion is that the symptoms are severe enough that they are causing some functional impairment. And the third level, which makes it a tricky diagnosis, is that we cannot find another clear explanation for the symptoms.

And this is where diagnosing depression becomes very difficult. Because when we do an evaluation for depression, there is no blood test, neuroimaging study, or psychological variable that gives us a positive result for depressive disorder. In other words, we cannot say, “Oh, you tested positive for depression”. What we can say is that you have symptoms that are consistent with depression, and we cannot find another reason for you to be experiencing those symptoms. The most difficult part of doing an evaluation for depression is ruling out all of the other possibilities that exist: endocrine, neurological, and immunological diseases, as well as general systemic medical diseases, other psychiatric disorders, or some substance abuse issues, can frequently be associated with the same constellation of symptoms as depression.

There are several treatment approaches that can be used. Much of the best evidence supports three main forms of treatment: the psychotherapeutic approach, the psychopharmacological approach, and the brain stimulation approach. The first form is psychotherapeutic interventions. There is a good evidence base suggesting that some specific forms of psychotherapy, such as cognitive behavioral therapy, can be effective in treating depression and preventing relapse. The psychopharmacological approach has grown dramatically since the 1960s. At present, there are several categories of antidepressant medications that have strong evidence suggesting their efficiency, including selective and epinephrine and norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors.

There are also older, less selective medications, such as tricyclic antidepressants or monoamine oxidase inhibitors which are also effective. More recently, there has been strong evidence suggesting that other classes of medications can be used in the adjunctive treatment of depression. For example, atypical antipsychotics have shown good efficacy in the adjunctive treatment of depression, although there are some concerns about worrisome side effects associated with them.

There are also other novel treatments that are used as augmentation, such as lithium thyroid augmentation, which are potentially useful in the treatment of depression. The third category is the somatic (brain stimulation) treatments. This would include electro-convulsive therapy (ECT), the longest-standing of the somatic treatments that are currently still in use. There is a rich history of ECT use in treating depressive episodes. ECT is still considered to be the gold standard in our field in terms of efficacy, especially for the treatment of resistant depression. There are other somatic treatments that have been approved by the US FDA, including transcranial magnetic stimulation (TMS) and vagal nerve stimulation (VNS). That may offer the patients and clinicians increased options. It is very important to match the treatment to the patient.

Each one of the treatment options has pros and cons, and depending on the severity of the depression, the urgency of getting a patient better, and the ability to tolerate potential side effects, you have to decide which is best for an individual person. In terms of having minimal adverse events and potentially positive long-term benefits, some of the psychotherapeutic approaches are very powerful and make a lot of sense as a first-line therapy for many people. The downside is that they tend to take a bit longer to take effect, and they actually require a proactive position from the patient because they are actually going to be involved and spend many hours engaging in therapy. But the risk is generally low with this form of therapy, and the evidence is generally good that it is effective and prevents relapse at high rates.

The pharmacotherapeutic approach has real benefits. It is probably the easiest for the patient to engage in and the least expensive of all the treatment options. But there are potential side-effects of the medication and the potential relapse if you stop the medication. In terms of overall effectiveness, the ECT is still considered to be the gold standard in terms of having higher efficacy rates for treating severely resistant depressed patients, but obviously, there is the cost and the potential risk of memory problems that need to be considered with that treatment.

I believe the past few years have been the most exciting time for the development of novel treatments for depression. There are a few things that came into place over the fifteen years that dramatically changed the way researchers study depression. One of the major changes is our willingness to accept the fact that we may not have been thinking of depression in a way that is most useful and helping us develop novel treatments. We used to think of depression as a single disorder that encompasses a wide range of symptoms spanning all the different spheres of cognition, emotion, and behavior. We tried to understand the biology of that broadly defined disorder for years. In the meantime, there has been parallel research going on – preclinical research in laboratories that have outlined very specific neurocircuitry that is linked to specific emotion, cognitive and behavioral patterns.

Using the findings from these preclinical studies, we can now start to develop new treatments based on what we know about the neurocircuitry of the brain and test if they are effective in treating at least certain components of depression. For example, we understand how certain brain regions are critically involved in generating the reward signal in the brain. Using that information, we can start to examine novel drugs that are affecting that reward circuitry and see if their effects are beneficial for the treatment of patients with anhedonia or the inability to modulate reward sensitivity.

Now, instead of thinking of depression as a single disorder, we try to understand how to develop treatments for the specific behavioral, cognitive, or emotional aspects of the disorder that we actually understand from neurobiology. The way we think is a major shift in the paradigm. Instead of thinking of depression as a single unified illness, we think of the neurobiology that underlies each component of it.

A lot of effort is being made in attempts to explore the pathophysiological processes that are seen in the brains of depressed patients or seen in animal models. Animal models of chronic stress – a useful model that seems to model depression as best as we can in non-human model species – suggest that the glutamatergic and GABAergic systems are critically involved in the pathogenesis of depression.

Using this information, we have developed novel treatments that are now being tested in clinical trials. And probably the most interesting at this point is looking for the drugs that modulate glutamate neurotransmission and, more specifically, the ones that modulate the NMDA receptor. We know that the drug Ketamine can modulate glutamate on a very short-term basis. But we also have very good pre-clinical data suggesting that after those more immediate effects on glutamate neurotransmission are seen, we see large changes in neuroplasticity. This means that we actually see changes in the way the cells in the brain communicate with each other. And it appears that some of these changes could be critical to the rapid onset of the antidepressant effect of drugs like Ketamine.

The future of the research on depression will probably follow efforts to understand the pathophysiological processes involved in the disorder and targeting processes with techniques that we already understand from neurobiology. For example, we would like to understand depression in the same way we understand illnesses in other branches of medicine, such as heart disease.

Once we started to really understand the pathogenesis and pathophysiology involved in the generation of coronary artery disease, we were able to make great progress in the prevention and treatment of cardiac disease. By understanding, what the pathophysiological processes are, we will be able to develop unique treatments to target these processes, minimize the long-term risk of depression, and also to develop more specific treatments.

Edited by Liana Khapaeva

Neurobiologist Madeline Lancaster on brain development, cerebral organoids and how close they are to actually ...

Psychologist Pamela Heaton on emotion recognition and musical abilities in individuals with autism

Neuroscientist John Krystal on alcohol's action on the brain, social and habitual drinking, and why some peopl...