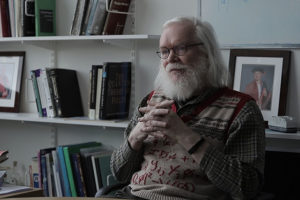

Dark Matter

Physicist John Ellis on discovery of dark matter, ways to look for it and what dark matter particles might be

Some years ago I was sitting next to a man at dinner: there was a dinner put on by my literary agent who is from New York, and he gets a bunch of interesting people around the dinner table in a restaurant in London. I started talking to this man and he said ‘I’m Brian Eno, the musician’. ‘I know who you are’ I said, ‘I’m an evolutionary biologist’. And we began talking as you do about music and evolution. I asked him, because he’s a smart guy as everybody knows, has anybody attempted to reconstruct the history of music rather like linguists have attempted to reconstruct the history of languages? After all, everybody in the world speaks a language and linguists make evolutionary trees out of those languages; everybody in the world in more or less every culture sing songs, surely you could be able to reconstruct the history of music too. And he said, ‘Well yeah, there has been one attempt by a guy called Alan Lomax’.

I said, ‘That’s mad but it’s brilliant, and what happened to it?’ He said, ‘Well, it sort of disappeared, everybody hated it, all his fellow ethnomusicologists hated it, it was all about numbers, they don’t do that’. And I said, ‘Well, I’m gonna find out more about this’. And I did, I went to New York and I got the data and I began working on this. It was wonderful, but I quickly realized that there has to be a better way than this data which you’ve got from undergraduates listening to music. We’re in the 2000s now, and in 2000s computers can do this.

And indeed, there’s a whole technology which is called ‘musical information retrieval’. It’s the technology that allows you to measure the properties of songs: what kind of chords they have, what timbres and rhythms they have and so on. And do it automatically. There’s a whole engineering discipline devoted to this. I made friends with some of those engineers and got to learn how to use their tools.

Then we thought, ‘Well, what are we going to study?’ The thing about these tools is that they’re mostly useful for studying pop music, they’re built for Western music rather than, say, the Inuit which is really just basically some men groaning to themselves while sitting on an ice floe. So we began to study pop, and not just any pop: we decided to study the Billboard Hot 100, 1960 to 2010: we downloaded 17,000 songs, we turned them into numbers and we began to tell the history of pop through numbers.

So it is why I claim (immodestly, perhaps) that I know more about pop music than anyone despite actually not even liking it that much. And the reason is simple: it’s because we all have opinions about pop and its evolution, and what happened when, and what was important, what were the relationships between musicians, but we just make all of that stuff up. I mean, there’s no reason to think that any of it is true. When were the greatest changes in pop music, when was it all happening? The answer is, ‘Well, usually when you were 17’. That’s because we’re just naturally embedded in pop, it’s part of the stories of our lives. So our point is to take it away from us and turn it into a science.

So we had the numbers, and we began by asking when did the great revolutions happen. We developed an algorithm for estimating revolutions, ‘a revolution detector’ we called it. The answer is that in American popular music there were three of them: in 1964, give or take a few years, in 1981 and in 1991. What were they? The 1964 revolution is when music becomes rock and roll: the British, the Beatles arrived in America are part of it too. In 1981 there was the rise of the drum machine and the synthesizer, it just flattens the musical landscape completely. And it’s important: everything from country music through to techno just sounds basically the same, like a Miami Vice soundtrack.

But the big one, the most striking thing (and we didn’t expect this, but maybe we should have in retrospect) is that the single most important phenomenon in the history of American popular music was the rise of hip-hop. It is just bigger than anything else that happened before or since. And it’s more radical too, because of course the thing about hip-hop is that it breaks the laws of music. One of the things our machine does is it detects chords, but when it tries it on hip-hop, lots of the time it can’t. Why? Because hip-hop is about rapping, it’s about spoken word, so the algorithm attempts to find a chord and it can’t. It’s just a complete transformation of the musical landscape. That along with many other things are the sorts of things that we’ve done in order to tell the history of American pop through numbers.

So one of the first questions we wanted to know about the history of American music (I suppose it’s an obvious one) is when did it change? So there are two views about how culture or how organisms change in the fossil record. One is that it all happens rather gradually; the other is that it happens by revolutions. We wanted to answer this question objectively: are there revolutions and if so, when did they happen? So we developed an algorithm called ‘a revolution detector’: it’s a little bit complicated, but the essence isn’t that hard. Essentially you measure the properties of a song in one year, you measure the properties of the song in another year, and you can calculate the distance, how far they are apart from each other. You do it for this year, this year, this year, this year, this year, and this year… Then you get a running average and then you can get an estimate of the difference, and if you find a big difference, our algorithm picks it up and tells that you’ve got a revolution.

But of course, given these numbers, we can do so much more. One of the things we can do is we can ask, what are the forces shaping popular music? So you can imagine that we’ve got this time-series data, we’ve measured these properties of the songs, let’s say the frequency of thrashing guitars, and so we can measure it over time. You can see its increase in the 60s, and then decrease, increase, decrease, increase… What you’re looking at is the rise, the fall, the rise, the fall and the rise of rock and roll. Or you can measure the frequency of songs in which there is a female voice singing in a melodic gentle fashion. Well, it turns out that that’s actually pretty stable over time.

And one of the surprising things we discovered is that although the songs are changing, the music actually stays the same. Pop music is amazingly conservative, and you can use various mathematical tests, various statistical tests to ask whether the music is changing or whether it’s in some sort of equilibrium. You can show that pop is never a random walk: it seems to be just changing in arbitrary directions but it’s not, it’s actually amazingly constant. It’s as if there are some forces which are shaping it all the time, and I think that’s true. Think of the example that I gave: songs by young women artists about love and loss, and boys that have done them wrong, and they’ve always been there, and as long as boys that do bad things to girls and leave them heartbroken there always be a market for those songs. There is as it were a niche, and it is that need, that role in the marketplace which just keeps the music constant for so long. The same is true for rock and roll: one of the things that’s so striking is that you can see rock and roll come, you can see it go again, you can see it come back again, and again… There’s an equilibrium which means although I cannot say that rock and roll never die, I can say that it’s very very hard to kill.

Physicist John Ellis on discovery of dark matter, ways to look for it and what dark matter particles might be

Neurologist Kevin Talbot on the history of neurological research, genetics of ALS and the modern view on the o...

Psychiatrist Guy Goodwin on the monoamine theory of depression, cognitive behaviour therapy and why some peopl...