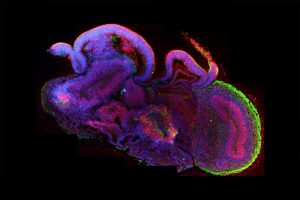

Brain Organoids

Neurobiologist Madeline Lancaster on brain development, cerebral organoids and how close they are to actually ...

So the question of why music is able to do such rich emotions in listeners is one that’s really fascinated psychologists and neuroscientists for a long time. In fact it’s fascinated philosophers for even longer. There isn’t any one strict definition of emotion in psychology, it’s a bit of a bugbear, but most researchers agree that it basically involves a number of key components. So it involves a so called cognitive component which is to do with you evaluating this situation or context, an event. There’s a psychophysiological component which is basically talking about the fact that your autonomic nervous system may show changes as a result of being in this emotional state, so your heart rates may change, your breathing may change, so it’s your autonomic nervous system. And there’s meant to be a sort of expressive behavioral and kind of packing them together component where if you’re scared your face will show terror, if you’re angry you’ll similarly have a very distinctive expression on your face. And it’s, as I said, behavior, so you might also act in a certain way in certain emotional states. So there’s this idea that you express and you behave and it shows that you’re in an emotional state. Finally there’s a feeling component and this is probably what most of us in everyday life think about when we think about the emotion. It’s like I feel sad, it’s the subjective report, the subjective experience of the person experiencing an emotion.

I guess you could say what we know is that emotions include all of these components; what we then mean by the music-induced emotions are emotional states that are induced by listening to music which necessarily have a few of these components. In terms of what they are we have emphasized the ‘induced’ because we want to emphasize the fact that it’s felt in response to music as opposed to us perceiving something in the music. This is an important distinction to make because often we’ll maybe perceive the music as happy but it doesn’t necessarily make us happy. So that’s an important distinction to make and one that researchers really care about when they look at music-induced emotions.

Why would we want to study them? Well, because research suggests actually that about half of our music listening episodes involve some sort of emotion, maybe not the stuff that really shocks the person but people will tend to report that they tend to feel some sort of emotion when they listen to music half the time. So one could argue that if you want to get a holistic understanding of emotions in general it’s useful to sort of better understand these parts of our emotional lives.

So when considering music-induced emotions it’s important to also consider how psychologists have talked about emotions in general. So they’re two very popular models and it’s almost naughty to repeat that because that’s sort of the one that psychologists repeat every single time, probably not news to anyone who cares a little bit about psychology. Basically it’s the basic model which is that we have these innate universal emotions: happiness, sadness, anger, disgust, fear, surprise. The idea is that across the world you see people being able to recognize these emotions: that’s what makes them so universal, basic.

The question is how well can they actually account for music-induced emotions? Maybe sometimes you feel happy when you listen to music, or if you feel sad somehow you feel a bit more sad, but how often you feel angry or disgusted? Not often. So the question is whether that would be a good way to think about music-induced emotions. Probably not or not alone.

Another very key model is the dimensional model of emotions that simply says two to three dimensions are enough to describe most emotion states. So the one dimension is valence which is basically how pleasant something is or how it feels, and then there’s arousal and it could be tension in energy or just plain arousal. But the idea is that it’s an indication of the states of your autonomic nervous system again, how your beating rate is, that sort of thing. But again, we could say: well, yes, that could help me tell you about how I feel about the music right now, I feel this is very nice, I feel quite calm as opposed to aroused but again, how much nuance is that in terms of describing what happens when we listen to music? What researchers of music psychology have decided is that these are interesting and useful but not enough. The trend has been to try to see if we can capture or acknowledge the wide variety of emotions that may be induced by music and really emphasize the fact that perhaps they aren’t the sort of utilitarian emotions that we experience in everyday life.

Utilitarian emotions are meant to be those emotions that help us adapt or adjust to events that are important to our survival and well-being. Take fear: you have to run away from the thing that’s fearful. Often there’s no real critical consequences of what we’re hearing when we listen music: basically it’s just the form that we’re enjoying and reflecting on. So the idea is that actually with music-induced emotions these are specific emotions that are sort of non-utilitarian nature, that sort of removed from self-concerns.

With that researchers have gone out and said: well, how can we find out what these are? And they’ve got to concerts outside of festivals and just ask people: what did you experience while you were in there? Or we can ask people in the house but the idea is to ask people. Then you try to see if there are any patterns in what people keep repeating as the emotions they felt. What’s interesting is you find emotions like nostalgia or tenderness and you’ll have something that’s close to happiness like joyful activation has been put forward for instance. But the idea is that you don’t necessarily see the sorts of things we see with the basic emotions.

Another interesting trend that you see in music psychology research on the topic of music-induced emotions is that people are now stressing not just what emotions you can have but how they come about, the mechanisms underlying them. The one influential paper for instance suggested that there’s about eight of them and what I’d like to do is just mention a couple. One of these mechanisms is musical expectancy and this is just the idea that especially in the case of tonal music, the music that follows these rules, you tend to make predictions about what’s going to happen next. We can’t help it, it’s the way our brain is structured. Of course when you make predictions sometimes you get it right, sometimes you get it wrong, sometimes you’ll have to wait to find out what the outcome is. What we’ve seen is that people generally enjoy this whole sort of predictive process. What’s more, when you are surprised, when you got it wrong you have a very distinctive pattern of brain activity that’s kind of cares about getting things wrong, and we also see physiological arousal when people get it wrong. So we see that actually this is a real mechanism by which these emotions are being induced, some sort of emotions is being induced by music.

Now another mechanism is empathy. Perhaps most of us think of empathy as something quite social: I empathize with you, with someone. But it’s really quite interesting for most people who care about the psychology of aesthetics or music and emotion et cetera to find out that actually the word ‘empathy’ came into the English dictionary through the word ‘Einfühlung’ which means ‘feel into’ and it was all about how we respond to art. It’s quite interesting to see that empathy is something that actually is now recognized as the way in which emotions induced in us through arts and music for example, but it was also what people were thinking in those days.

What’s interesting is we’ve seen studies that show for instance just generally how empathetic you are in everyday life, if you’re just someone who emphasizes a lot, this is able to predict the extent to which you’ll be moved by sad music, for instance. So you hear a sad song and you’ll say: ‘Oh gosh, I’m so moved’ and it’s because perhaps you’re empathizing with what you seem to think is the story behind that. Similarly we’ve seen another type of empathy that is not very emotional but rather a bit more cognitive. So it’s a weird thing, it’s cognitive empathy and what people are shown for instance is that when you’re listening to music that you think has been composed by a real person compared to when you think has been composed by an algorithm, a whole brain network that cares about attributing mental states to other people, reading their mind almost, lights up suggesting and again when we listen to music we can’t help but sort of wonder, reflect on what they might be trying to tell us or just mental states they were in.

So in terms of research music-induced emotions that’s been this interest in what they are, how they seem to be induced. And of course there’s a whole range of different methods you can use to investigate them.

The work I do I guess is sort of more in the brain side. I care about how the brain’s emotion network, areas that we know to be involved in processing emotions, mediating emotions, how they are modulated by simple things like consonance and dissonance or the surprise that we feel in response to music. I carry out this research sometimes with a very unique sample of participants which are people who have to have intracranial electrodes in their brains. Normally we just measure from the scalp (psychology students too often), but sometimes we have access to patients who are willing to take part in our experiments who just happen to have electrodes in their brain for surgical procedures they’re about to carry out. With that data we can really get some very fine temporal resolution on brain areas that are very deep in the brain and that we know to be involved in emotion. That’s been some of my research. In that case I tended to use very simple stimuli, the idea being that it’s very rich datasets, you use simple stimuli if you can. Of course we want ecological validity, so in other studies we’ve asked people to come into the lab with their own music and then we’ve asked questions like ‘Bring in music that there are moments where you find that moment is really beautiful’ and then we’ve studied how they describe those moments, how they respond physiologically to those moments and actually what’s happening in the music in those moments.

We’ve seen some very interesting patterns. Sometimes these moments are very arousing and we see that they report them being very arousing and then we see that in fact their bodily responses reflect that and we also see in the music that there are clear structural changes at those moments. We have other examples where they report them very calm and interestingly we don’t see any huge structural changes: if anything we just see increased smiling which we think has something to do with the fact that actually it’s so easy to process and somehow they are seeing the beauty in that ease, processing fluency. So in those sorts of studies we’re moving away from looking at the fundamental features of music to sort of looking, make more emphasis on the experience and trying to understand basically emotions in what we hope is similar to what our experience in everyday life.

Neurobiologist Madeline Lancaster on brain development, cerebral organoids and how close they are to actually ...

Neuropsychologist Chris Frith on mirror neurons, compassion, and how it depends on the sentiment towards the s...

Neuroscientist Karl Friston on functional specialization of different brain areas, brain hierarchy, and the co...