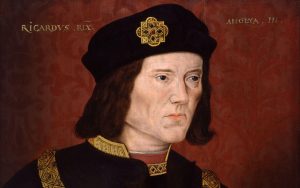

Richard III

Historian John Ashdown-Hill on one of the most controversial figures in English history, Shakespeare's dark im...

It’s a fascinating topic as to how the scientists entered Russia, entered Russian culture. We’re familiar with the idea that science was introduced into Russia by Tsar Peter I, Peter the Great, that Russia didn’t have a scientific tradition before the 18th century. During the 18th century, Peter introduced science through an Academy, which he founded and which opened in 1725. But how the Academy and how the sciences actually became a part of Russian culture was a complicated story. It was quite a fraught affair. One of the fascinating things about that story is that spectacle and performance were key elements of the way that scientists who were involved in it managed to get the Russian government and the Russian court to take the sciences seriously.

Peter the Great wanted to bring more Western European style culture to Russia partly to improve the military, who’s involved in the Great Northern War with Sweden, and he had to modernize the army to win that war. So, he founded a city Saint Petersburg and introduced many different reforms that europeanized Russian culture. One of those was to introduce Western science. He organized with the help of the German philosopher Gottfried Leibniz and his students and followers an Academy of Sciences that opened in Saint Petersburg in 1725. The people who were brought there came from Germany, from France. They were very well paid, some of them were quite famous, and all things looked good. But unfortunately, Peter died, and so he, as the main patron of the Academy, was no longer there to protect it.

The academicians very quickly tried to figure out ways to enamor themselves with the Russian Court, which at this time – and we’re talking about the 1720s and 30s – was located in Saint Petersburg. For a while they were okay, whilst Peters Widow Catherine was on the Russian throne. But at the beginning of the 1730’s, there was a new empress Anna Ivanovna. She didn’t automatically have any particular interest in the sciences.

So, what should you do? How should you secure your Academy in this situation and your scientific activities? Well, the academicians were led by a man named Johann Daniel Schumacher. Schumacher was originally from Alsace and he’d come to Russia as Peter’s librarian and chief scientific adviser, and he was the secretary of the Academy, and he was a very smart man in understanding what needed to be done to try and secure the place of the Academy and the sciences in Russia. I think, what Schumacher realized was that doing science was not going to get the court very interested in the academy. So, whereas in the 1720’s people had done lectures about Newtonian physics and Leibniz mathematics and so on, that really declined in the 1730’s. Instead what Schumacher concentrated on was hiring people who could perform activities that would be of interest to Ana Ivanovna’s court chief.

You needed expertise in order to write those narratives and understand how to compose stories using all of the symbolic iconography that fireworks displays required. In Russia there was no one who could do that. Schumacher understood that, and so he started to hire new academicians who were really good at designing fireworks. He found a gentleman named Junker who could do that, and another called Stahl. Junker and Stahl, and others in the Academy started to produce these very elaborate compositions of fireworks for staging to celebrate the Russian Court and the Empress Anna Ivanovna.

This, in fact, is one of the things that the first Russian scientist Mikhail Lomonosov did as a young man. He would design illuminations and fireworks for the court. Schumacher also hired people to write poetry for the court, odes to celebrate the Empress, for example, and all kinds of artistic departments that would produce the kinds of things that the court might be interested in having. This was a very successful strategy.

By the end of the 1730-1739, the Academy was in a very good position because it had set itself up to provide all of these services to the court who ultimately controlled its fate. The court was happy to support it. But then something unfortunate happened – Anna Ivanovna died and was replaced after a little while by the daughter of Peter the Great, Elizabeth Petrovna, Elizaveta Petrovna. She became Empress Elizabeth, and she really had a problem with Anna Ivanovna and foreign courtiers who had grown up with her and become a part of her retinue led by a man named Ernst Baron, who was considered an absolute disaster for Russia.

Elizabeth set about getting rid of all of the nobles and anyone closely associated with Anna’s court and replacing them with Russians and French individuals who were in her favor. That was very bad news for Schumacher because he just spent ten years building up a close connection to Anna’s court, because he wanted the Academy and the sciences to survive in Russia. In fact, Schumacher was quickly arrested under Elizabeth’s rule, and there was an investigation into him in which he was accused of all kinds of terrible deeds, and embezzlement, and corruption, and so on.

It turns out that in the end Schumacher survived partly through his connections to people like Jacob von Stahl, who was one of these designers of court spectacle. One might argue that what Elizabeth realized over time, or what her courtiers realized over time was that they still needed the spectacular skills of the Academy albeit that they should be transformed to celebrate Elizabeth and not Anna. So, Schumacher ultimately was released and in the early 1740s, or in the 1740s a charter was established for the academy, which set in law that the Academy had a right to exist and operate on particular terms, and that was a key moment because it meant that the academy was finally secured in Russia. So what we’re seeing in this story is the way that spectacle and the ability to design fireworks of all things actually played an important role in securing a place for science in Russian culture.

Historian John Ashdown-Hill on one of the most controversial figures in English history, Shakespeare's dark im...

Archeologist Tim Reynolds on Mousterian tools, cross-species interactions, and Neanderthal language

Shlomo Izre'el on the myths about the Hebrew language, its relations with Yiddish, and how children teach thei...