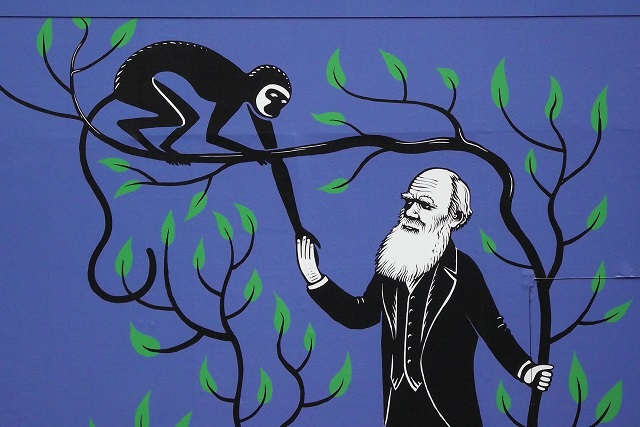

Aristotle’s Biology

Evolutionary biologist Armand Leroi on the first studies of animal anatomy, ancient works on nature and the in...

Darwin described evolution as “descent with modification”. “Descent” is the passing of information from one generation to the next, and “modification” – that’s the fact that the modification of that copying process is imperfect – there are errors. You can see descent with modification in many-many different ways; you can see it, for example, in language. If I listen to my students in London now, they all speak with the same accent, which is what used to be the working class or the Cockney accent in London. Now, if their grandparents heard them speaking like that, they would be shocked, for it was not seen as correct English. So even the English language has changed quite notably in 20-30 years. That is evolution – descent with modification.

We could rephrase this expression in three more modern words, which is evolution = genetics + time. Genetics is passing DNA-based information from one generation to the next, modification in a moment of time – that is mutation. Mutations, or errors, happen all the time. Everybody reading this piece would be a different person than when he started because they would have had mutations in their cells. So evolution is bound to happen.

One can always find the theories of change. If you go to the ancient Greeks, there was a philosopher called Thales, who thought that everything was water and everything emerged from a primordial substance called ‘water’. That is not exactly true, but it is an evolutionary theory. One can trace it all the way through.

In the 19th century, there also were evolutionary theories. There was a man called Robert Chambers, who wrote Vestiges of Creation. In this book, he claimed that, in fact, life had changed: there had been an alteration of primordial kinds of humans, cats, and dogs, but he thought that it was due to nature working out God’s plan.

If you go to Paris, to the garden called Jardin des Plantes, you will see a statue of the ‘founder of evolution. You might think that it is Charles Darwin, but it is not; it is Lamarck. Lamarck is well-known for his inheritance of acquired characteristics, and Darwin himself admits that Lamarck is the author of the first modern version of evolution. Lamarck famously thought that evolution is a kind of mental process and that animals were striving to get better. So the idea was in the air.

He lived in the times of the French Revolution. He was a protege of a very famous biologist called Buffon. Buffon was a great systematist – he went out and studied animals. And he wrote an enormous book, Histoire Naturelle; there were many-many volumes in which he simply described animals across the world. He tried to classify them, and he classified them quite predictably on the level of increasing sophistication. And he had all kinds of strange ideas, and one of the strangest ideas was that in the Americas, everything went wrong. Europe was the land of advance, but the New World was the land of decay. He was convinced that all the creatures in the New World had stepped off the ladder of evolutionary advance and begun declining. And Thomas Jefferson, one of the earlier American presidents, was infuriated by this. To prove that Buffon was wrong, he caught a moose, an enormous deer, stuffed it and sent it to Buffon, and said, ‘Look at it, it is bigger than anything you have got; it has not declined’. That did not change Buffon’s mind.

Lamarck was a disciple of Buffon, and he took the idea of advancing further. Buffon had an idea that somehow evolution was chemistry; it was going to happen – if it happened on Earth, it was bound to happen on any other body as well. He assumed that there would be elephants and rhinoceroses on the Moon. Lamarck’s idea was much the same. He is mocked for the idea of the inheritance of acquired characteristics. When schoolchildren are taught about Lamarckism, they are told about giraffes – about the idea that giraffes have long necks because they want to reach up to trees, so the next generations would have longer necks. In fact, Lamarck only mentions giraffes once in one sentence. He talks much more about the feet of birds. Birds that land in water want to stand out of the water, so the next generation will have longer feet. This is called the ‘law of necessary progress’.

Lamarck is now mocked for his theory of the inheritance of acquired characters, but in fact, Darwin believed the same thing. But what Darwin hated about Lamarck, although he is quite polite about that in The Origins of Species, was that somehow there was this notion of necessary progress – things were bound to get better, and the only way was to improve. But Darwin wrote about it in his letters – “never say higher or lower”, i.e., there were no higher or lower creatures because if you take any animal – it is just as high a creature as a human.

Interestingly, the word ‘evolution’ does not appear in The Origin of Species, and the word ‘evolved’ only appears once – it is the last word in the book. The word ‘evolution’ initially meant ‘unrolling’, as in ‘unrolling the scroll’, and it is as simple as that – you are unrolling a series of errors. That is what evolution is. It is an old idea, but Darwin’s contribution was to add a second part to that, which is natural selection. Natural selection is in terms of inherited differences in the ability to reproduce. If you inherit a mutation that makes it more likely that you will survive, find a mate, and reproduce compared to the people who have not inherited that mutation – that mutation will become more common in the next generation. And over the years, Darwin argued that the accumulation of new mutations would produce new breeds of animals and, in the end, new species.

What drove Darwin to write The Origins of Species was a letter from the English naturalist named Alfred Russel Walles. He was in the Malay archipelago, and he wrote to a friend of Darwin with an idea. And Darwin opened the letter and said, ‘All my priorities are shattered; somebody had already had the same idea’. He then presented the paper to the Linnean Society in London, and they announced the joint theory – the Darwin-Walles theory. And Walles did not know anything about this, and many people said that Darwin cheated that he stole the idea from Walles. But this is completely not true, for we see the idea of natural selection in Darwin’s unpublished works 20 years before The Origin of Species. Then he rushed in and wrote The Origins of Species in a year and he called it a sketch. He thought that this was not good enough, that there was not enough evidence. And then he just lays out his theory, and he does it in a very clever way because he calls the book a ‘one long argument’.

He starts with the most obvious observations. Which is: if you go to a farm, to the cow pastures, you will find cows of two kinds: some breeds give milk, and some breeds give meat. And if you look at history, you will see that both those kinds have emerged from wild cattle, or oxen, as we call them, and farmers selected some of them with more milk and some with more meat. And almost magically, these new breeds arise. This is a descent with modification and natural, artificial selection.

Then he does the evolution that occurs in nature. And he suggests that the same kind of thing happens in nature, and he talks about the struggle for existence. And this is, again, a very old idea first proposed in modern terms by an English clergyman – Thomas Malthus. He said that the number of people would go up geometrically (2, 4, 8, 16, etc.), whereas the amount of food would go up only arithmetically (2, 4, 6, 8, etc.). So inevitably, not every human or animal born will be able to survive – there will be a struggle for existence. And he was right there.

Darwin read that and wrote in his diary: “At last, I have a theory to work with”. In other words, he had a theory that there is a struggle for existence and not every animal can survive, and he observed that some of them inherit traits that increase their probability of survival. And then, he goes on with a huge mass of evidence about the geography of life, animals on islands, mental evolution, which he calls ‘emotion’, domestication, etc. And then, two of three pages to the end of the book, he goes to the most frightening part of evolution – namely, he writes, ‘light will be cast on man and his origins’. And he did not dare to say anything more about that. Later he wrote a book, On The Descent of Man, where he lays out his case: humans, just as much as cows and other animals are evolved by natural selection.

We know that Darwin received at least 14000 letters in his lifetime. People wrote to him with objections about his theory. Many wrote something like ‘I thought about that first’, and Darwin was quite polite. But there was one particular man called Thoman Matthews, who wrote an indignant letter saying: “I thought of that in the 1830s, and it is in my book, which is called On Naval Timber”. Matthews was a Scot, he worked on growing trees, and in just one paragraph of his big thick book on growing trees, he said that “sometimes some trees will grow straighter, thicker and more beautiful than others. And if you breed from these trees the next generation will improve”. And this is the theory of evolution, but it is hidden away in this large book on growing trees. To him, Darwin responded: “I am very sorry, I have not read your book, but you were right; you had the idea before me”.

And another letter that distressed Darwin concerned the age of the Earth. The physicist Lord Kelvin tried to work out how old the Earth was, and he did it by measuring the temperature as he went down the coal mines. He suggested that if you want to work out how rapidly the Earth was cooling, based on his observations, it seemed that the Earth could be at most 2 million years old. And Darwin knew that this was not enough time for his theory, and this worried him too. Now we know the Earth is much older than that, so this argument does not stand too.

In 1859 the theory was quite quickly accepted, although many people, especially religious people, had problems with it. Interestingly, with the rediscovery of Gregor Mendel’s work – the idea of genes as particles and the discovery of mutations – ‘errors’ in the DNA – Darwinism was kind of thrown out of the window. They thought that the gradual change and an accumulation of slight errors contradicted the theory. Evolutionary change is like the mutations that we see in fruit flies – one time, you have got a red fruit fly, and then suddenly, you have a white fruit fly. And that is evolution caused by leaps. So in the 1920s and later, Darwin was almost forgotten. It was said that it was a theory that had been of interest and was no longer considered to be so. And then, slowly, the two came together into what is called Neo-Darwinism in the 1950s-60s. People realized that you could accumulate slow genetic changes that lead to large changes in the traits.

Evolutionists and geneticists still have a slightly uneasy relationship; there are still arguments about big mutations versus small mutations, how often mutations happen, and why is the mutation rate so low – around 1 in a million. But we know that nearly all mutations are repaired. The question here is – why doesn’t it fix all mutations? We do not know.

One of the biggest challenges for the theory of evolution is the one that Darwin himself faced – which is the origins of species. Darwin’s book is called On the Origin of Species by Means of Natural Selection or The Preservation of Favoured Races in the Struggle for Life – that is the full title of The Origins of Species. But if you read it, there actually is not much on the origins of species because Darwin talks a lot about natural selection, islands, geography, and so on, but he is struggling with the idea of what species are. That is what evolutionary biologists are still struggling with because the nature of genetics is you make crosses – you can cross individuals within the species, say, two dogs, but you cannot cross dogs and cats. So you cannot study species in a way that you would really like to study species – by doing genetics of that.

You can find some places where there are hybrids between different species, for example, in a lab. For example, you can cross the two distinct species of fish – swordtail and platyfish – in a laboratory to get hybrid offspring. However, in the later generations, one of those fish will get black spots, and then in further generations, those with black spots will get skin cancers. This is because, in cell division, you have got ‘accelerators’ (oncogenes) and ‘brakes’ (tumor suppressor genes) that work together to control it. If they go wrong, you get cancer. In these fish hybrids, the ‘accelerators’ received from one species are more powerful than the ‘brakes’ got from the other, so genes from two different species do not seem to work together. Thus the question is: what are species: how do they emerge, and how different are they?

Another major question is: why does the genome look the way it is? If you were a strict Darwinian, you would expect that the genome, albeit somewhat imperfect, would be like a badly designed machine that did the job, although it could do it better, still. A long time ago, we assumed that to make a creature as wonderful and attractive as a human being would take millions of different genes, but in fact, we now know that there are about 32000 – far fewer than we expected. That is not much genetic information for evolution to work with.

Even more annoying is to find that around 99% of our genome is what is called ‘junk DNA’, which we got from parasites, repeats, and a lot of it does not work. We used to believe that it is useless, but now the research says that it may also have some function. There are some fish that do not have any ‘junk DNA’; they just have their 23000 genes, and this is it. Humans have lots of junk and they also seem to be doing quite well. At the moment, it is hard to explain that in Darwinian terms.

Edited by Ksenia Vinogradova

Evolutionary biologist Armand Leroi on the first studies of animal anatomy, ancient works on nature and the in...

MIT Lecturer Vyacheslav Gerovitch on Sergei Korolev’s design bureau, the leadership of the Soviet cosmonauts, ...

Bioengineer Ali Khademhosseini on the challenge of biocompatibility, biological inks, and printing organs on t...