Empathy

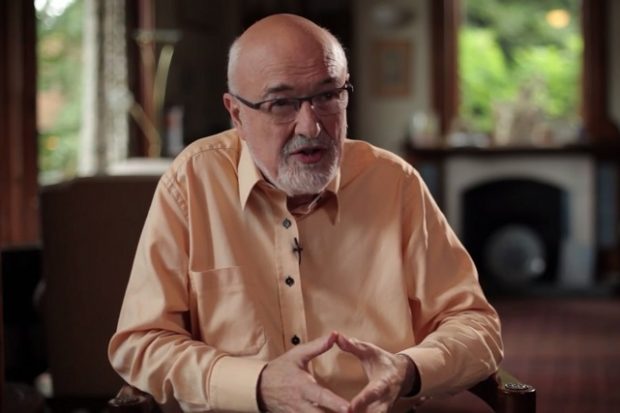

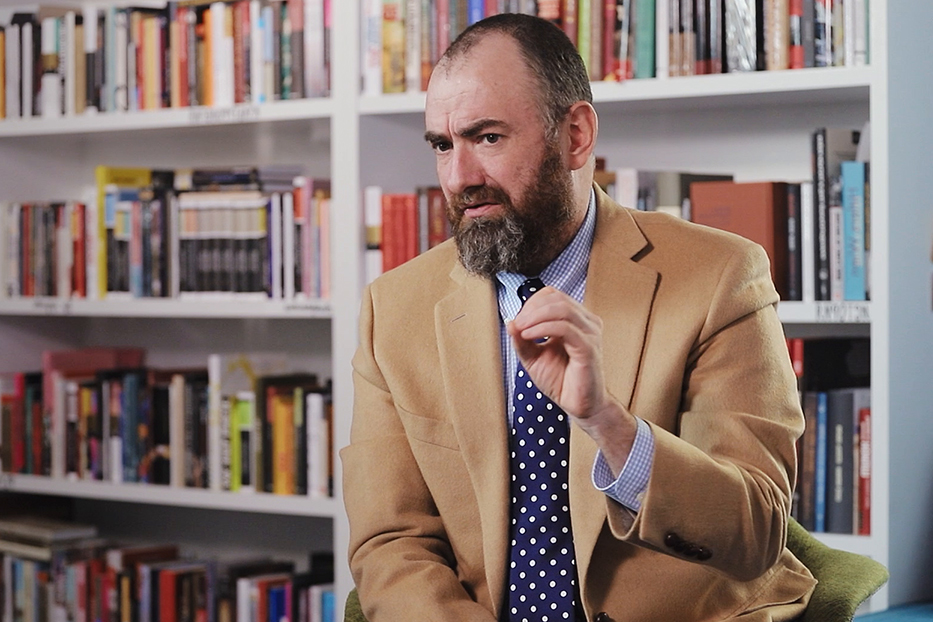

Neuropsychologist Chris Frith on mirror neurons, compassion, and how it depends on the sentiment towards the subject and his race

videos | May 29, 2017

One of the major topics in social cognition has from the very beginning been the study of how we recognize the expressions in faces. There are the five basic expressions which include happiness, sadness, disgust, fear and surprise. When brain imaging was added to the mix it was possible to identify brain regions that were particularly concerned with these kinds of expressions like the amygdala is very interested in fear, the insula is very interested in disgust. But also it was found that our response to emotional expressions in faces is a part of the mirror system where we have common neural basis for recognizing something and for doing something. When I see a happy expression or a fearful expression the same bits of a brain light up as when I feel happy or I feel fear. People immediately recognize that this might be an interesting basis for empathy, but it turns out that empathy is actually rather complicated. One of the things I found fascinating is that word does not come into the English language until the beginning of the XX century which is remarkably late. It comes from the German word “Einfühlung” which is to feel yourself into a situation, and people used to talk about how you would appreciate art because somehow the picture you are looking at causes you to feel the emotions that the artist is trying to present to you. The discovery of this mirroring system in the brain seemed to be a direct representation of this kind of experience.

Probably there are at least three levels of empathy. There is emotional contagion, where I feel your emotion even though I am not aware that it is your emotion on the time I am feeling it. There is ‘I feel your emotion and know that it is your emotion and not my emotion although I am reflecting it to some extent”. At the other extreme there is “I know that you are having an emotion and as a result of this I want to help you, so if you are feeling sad I want to cheer you up, and it would seem to me the case that if you are feeling sad and I start feeling sad as well, this is probably not the best way to achieve this”. And there are even more important situations whereby if I see an angry expression it is probably not ideal to be angry myself, so things become more complicated as soon as you bring in these higher level cognitive processes into the study of empathy.

Another mirror system exists for pain which again depends in part on facial expressions. If I see someone with an expression of pain I will also feel that emotion, but to do it more directly we can show people receiving painful stimuli. This has been done in various ways. For example, you are in the scanner and on the screen in front of you, you see somebody’s hand and a needle sticking into it or a cotton bud stroking it. An interesting thing here is that when you see a needle sticking into someone’s hand the areas in your brain that responded pain (anterior cingulated and anterior insula) light up and these are the same areas that light up when you yourself have a needle stuck into you in the scanner. There is this overlap, and they will even light up when you are simply told that the person is going to receive a painful stimuli when the light goes on, so simply knowing when your companion is going to receive this painful stimuli you see a painful response in yourself. Again, this can be an example of empathy.

But again, life is more complicated. You can ask the question – ‘does it matter who you see getting the painful stimuli?’ One experiment we did with Tania Singer, she manipulated people’s belief about who it was that was getting the pain. So basically she made them believe that this was a nice person or nasty person. This was done by actors who were brought in for experiment to play a game with the subject of the experiment or the participant of the experiment. One actor was told to cheat and the other actor is told to be cooperative and they very rapidly get a reputation of being nice or nasty. Then, when you see them getting the pain in the scanner you are much less responsive if it is the nasty person getting this pain, particularly if you are a man. There was even some suggestion that men when they saw the nasty person getting the pain actually their reward system of the brain lit up, that is one aspect which we may not be surprised about.

A very tough question in all the social cognition is the extent to which these processes are innate rather learned from our culture and our environment. I would say that (this is me speculating, all those sorts of experiments that I would like to do in the future) we all come from the factory as it were hardwired, but this can be overcome. Very young infants already show signs of prejudice, but depending on the culture in which they find themselves this can rapidly be overcome. There is a nice experiment of a much simpler kind about faces again, with the new computerized faces you can morph between faces of different races or people from different countries. So you can have a Caucasian face at one end and the Japanese face at the other end and you can have all the possible intermediate faces. You can then ask people in different cultures in a sense where the cutoff is. If you ask people in America: at what point does it no longer look like an American face it is much closer to the American than it is to the Japanese. If you ask people in Japan where does it change from a Japanese face to a Caucasian face it is much closer to the Japanese end. This is an example of sort of prejudice, but this is purely created by the environment in which you find yourself so if you take an American from America to Japan where he is now surrounded by Japanese faces this neutral position moves because it is influenced by the majority of the people that you see. I think this is a nice example of how these factory settings, as if it were, can be modified by the environment in which you find yourself.