The Benandanti

Historian Carlo Ginzburg on the benandanti witches, clashes between medieval peasants and inquisitors, and the...

How do the consequences of World War I reflect on global politics of the 21st century? Why was the Russian Revolution a part of global history that started in 1914? What makes the European Union a pacifist political program? These and other questions are answered by Jay M. Winter, Charles J. Stille Professor of History at Yale University.

What happened at the end of World War I was a collision between Islam and imperialism. That collision was because the victorious allied countries intended to carve Ottoman Turkey into sectors of influence or control, where the Greeks would have their part, the Italians – theirs, the British – theirs, the French – theirs. And maybe the Americans would have some part of Armenia. But in no sense was the Middle East going to be a place where independent nations would exist; Empire survived World War I in the Middle East. And by doing so, it created a series of puppet leaders, the best well-known of which is King Farouk of Egypt but there are many others, who served as agents of imperial Britain or imperial France and whose position was deeply suspect by Muslims of a devout and radical kind. Where was the future of Islam? What would happen to women in the family? Would Sharia, the Muslim law, operate? All of these questions were now unclear and uncertain. And a group of radicals met in the late 1920s in Cairo to do something about it. They created a group called “The Muslim Brotherhood” and that brotherhood in due course spawned the radical groups that assassinated Anwar Sadat in Egypt – the man who made peace with Israel – and created Al Qaeda and the Islamic State movement today. There is a direct line between the First World War and the violence going on in Syria, Lybia, Yemen and many parts of the Arab world today.

In my view, what happened in the First World War was the creation of a monster state. States in the First World War had power over everybody and everything: they had communications that could allow them to find out about you, or your family, or your uncle living in the mountains and reach him. The hand of the state was everywhere. The power of the state was everywhere and wartime law became what the state wanted it to be, so anyone could be arrested. This powerful authoritarian state combined with the brutalization of soldiers who fought for four years – the Russian army lost two million soldiers in the First World War and then these casualties were probably of the same order in the Russian Civil War – a brutalized population, a hungry population facing famine in hands of an authoritarian state is the direct outcome of the First World War. The crimes of Lenin and Stalin could never have happened without the First World War. There would never have been a Russian Revolution without the First World War and the same is true for Nazi Germany. The monstrous regime that the Nazis created was a direct outcome of the German defeat in the First World War, followed up by the weakness of democracy. So, the authoritarian character of the Russian twentieth century, the crimes of the Gulag came not out of Russian history but of global history. It came out of a global explosion called the First World War, in which states with massive power were able to operate without any legal control.

[European union] is a way of organizing power without big armies. Now European nations spend less of their national budget on armies than ever before. There are smaller numbers of soldiers as part of the workforce of Western European and Eastern European countries in the European Union than ever before. It is a place where, yes, war did break out in Yugoslavia but in the countries conspicuously not part of the European Union and in a country that remains outside of it because of the consequences of the bloodbath of 1990s in former Yugoslavia. So, what I think we can see is that the state we all live in, with enormous power, the ethnic quarrels that we can see especially in the Middle East but not only, the Islamic radical hand has extended well into the Russian republic, from Chechnya, or from Georgia, or from other parts of the Caucasus. And indeed the question of Europe and what Europe means comes directly out of the First World War. My guess is that the history of the First World War is the best way for students to realize that Russian history is European history and it started to go wrong in 1914, and it stayed wrong for a long time.

Historian Carlo Ginzburg on the benandanti witches, clashes between medieval peasants and inquisitors, and the...

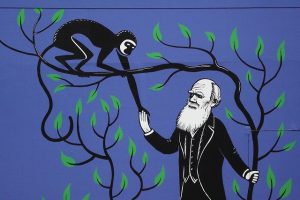

Biologist Steve Jones on Darwin, Lamarck, and the uneasy relationship between evolution and genetics

Historian Rory Naismith on the monk Ælfric Bata, the formation of the English monetary system, and the silver ...